Part 2: Measuring 'noise' when assessing school shooting threats

Overview of survey questions, fictional scenarios, and methods used to measure the 'noise'--or undesirable variability in decision making--when police officers assess threats.

Nobel prize-winning economist Daniel Kahneman died last month. I started the research for this paper when I read his book, Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgement, in 2021. His last long form interview was on Freakonomics Radio about Noise.

Noise is the unwanted variability in decisions made by experts who are looking at the same information. Translation: Two people see the exact same thing differently despite expectations that their decisions are made consistently.

This series of Substack articles is based on a survey that I conducted after reading Kahneman’s book Noise in 2021. I cowrote a subsequent academic journal article on the survey results with Dr. Jillian Peterson, Dr. James Densley, and Gina Erickson from The Violence Project.

In Part 1: Impact of 'noise' on assessing school shooting threats, I provided an overview of what the concept of ‘noise’ is and why it needs to be measured.

Part 2 (this article), covers the methods, survey questions, and school shooting threat vignettes we created to measure noise. This process is called a ‘noise’ audit.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Hamline University and standard ethical principles were followed regarding voluntary participation, active and informed consent, the right to withdraw, confidentiality, and data protection.

In August 2021, at the start of the new school year, an electronic survey was sent by email to 600 alumni of the Center for Homeland Defense and Security who were affiliated with a law enforcement agency. The survey was also sent to all members in good standing of the National Association of School Resource Officers, a professional association of about 3,000 school police officers.

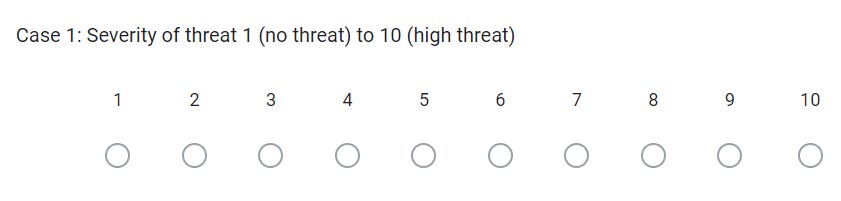

The survey yielded responses from 245 law enforcement practitioners directly responsible for assessing threats. They rated on a Likert scale from 1 (no threat) to 10 (high threat), the severity of six fictitious vignettes constructed from common themes identified in real school shooting threats. For each scenario, 14 common response actions were also selected.

The vignettes used in this study are representative in both topic and level of detail of the types of threats schools are receiving daily via:

Social media accounts

Telephone calls

Postings on an online community message board

Drawings or graffiti

Verbal reports by a student to school officials

Threats captured by a formalized threat reporting system

School shooting threat vignettes

Each of the fictitious scenarios varies in time, day of week, specificity, and school level to capture extraneous factors that may influence the perceived severity of the threat. For each scenario, the respondent needed to select a value from 1 (no threat) to 10 (highest threat).

The text of the vignettes reads:

Case 1: Monday, 8:00 PM: A Twitter account with 0 followers posts a message stating there will be a shooting at Oak Creek Elementary School in your district at 9:47 am tomorrow.

Case 2: Sunday, 2:00 PM: 9-1-1 hang up call from a voice that sounds like a teenager threatens a shooting at Walnut High School in your district. No date or time is given. No answer on call back. Number traces to an online phone service with no registration information.

Case 3: Wednesday, 11pm: Multi-page manifesto is posted to a community message board from an anonymous account. The document outlines a plan to attack a high school and names specific students as targets, and includes a list of weapons. No date or time is specified for the attack.

Case 4: Tuesday, 10:00am: A teacher at Oak Creek Elementary finds a student’s drawing of stick figures portraying a school shooting in a trashcan. The teacher does not know which student drew the picture.

Case 5: Monday, 11:00am: Student shows school resource officer at Riverbend Middle School in your district a SnapChat thread being circulated by dozens of students. The thread shows photos of students with either a “heart” or “gun” emoji under their photo. Students on the thread are continuing to upload additional photos.

Case 6: Thursday, 2:30am: Via online threat reporting tool, an adult woman reports that her ex-husband is planning to shoot up the school. Records show he has no criminal history or disciplinary history as an employee, but multiple weapons are registered in his name. Prior to divorcing, the couple retired from teaching at Oak Creek High School. The man named as the threat is now married to a current Oak Creek High School teacher.

For each case, respondents were then asked to select how they would respond to the threat from a menu of options: (1) immediate lockdown; (2) evacuate building; (3) cancel classes for the day; (4) cancel classes tomorrow; (5) dispatch officers for “active shooter”; (6) deploy officers for increased school presence; (7) email school employees; (8) email parents and students; (9) send automated emergency alert; (10) issue press release/official communication from social media accounts; (11) question student/others involved; (12) arrest student/others involved; (13) refer to mental health or social services; (14) take no action.

Respondents were invited to check all responses they felt applied. Respondents also had option to include qualitative notes on how they perceived the threat and use a narrative text field to explain why they chose the response options that they selected.

There were also demographic questions on individual and agency characteristics including gender, race, status as a parent, grandparent, aunt/uncle, or none to children enrolled in K-12 schools, and whether respondent has responded to a school shooting. Questions asked about agency and community characteristics, including geographic location (region of country and rural, suburban, or urban setting) and job classification (job title, agency type, and whether the agency has responded to a school shooting).

Alignment to real world threats

While the details of each vignette portray fictional circumstances, the mode and substance these cases mirror real-world shooting threats received by schools. For each of these situations, someone had to make a quick decision about how to respond with very little information available.

Case 1 aligns with an anonymous Twitter threat sent to a Rutherford, NC high school.

An anonymous threat called into an Oakland, MI high school outlines the circumstances for Case 2.

Case 3 draws from a manifesto written by a former UCLA professor who threatened a shooting on campus.

The drawing in Case 4 is similar to the doodles on a math test found by the teacher at Oxford High School hours before a school shooting.

Case 5 parallels a message sent on SnapChat by a student at St. John the Baptist Parish public school in Louisiana.

A teacher’s warnings about violence at the school threatened by her ex-husband in San Diego, CA is the framework for Case 6.

Findings and Solutions

This research paper has too much information for one Substack article so I’ve broken it down into four parts that will be published over the next three weeks (unless there is a major incident that requires timely and focused analysis).

Part 1: Impact of 'noise' on assessing school shooting threats

Part 2: Measuring 'noise' when assessing school shooting threats

Part 3: Results from 'noise audit' when assessing school shooting threats

Part 4: Ways to reduce noise when assessing school shooting threats

Thanks for reading, please share with other people who care about school safety and let me know what you think.

David Riedman is the creator of the K-12 School Shooting Database and an internationally recognized expert. Listen to my recent interviews on Freakonomics Radio, New England Journal of Medicine, and Iowa Public Radio after the Perry High shooting.