Wounded victims can die when plans are based on the 'second shooter' fallacy

During a school shooting response, current policies direct EMS units to wait outside while police search the school for a second attacker. This delays care for critically wounded victims.

"We used to talk about getting care to a patient in the ‘golden hour’. Now we are focused on the ‘platinum 10 minutes’ when the combat medic provides immediate lifesaving care." - Col. Bruce McVeigh, Army 1st Medical Brigade

Every emergency response can be complicated by hypothetical scenarios involving a second hazard. Here are a couple of highly unlikely situations with an unexpected secondary risk that I encountered as a firefighter and EMT:

Outside debris fire was started by a man who is high on meth and roaming the property with a machete. I responded as the lineman on an engine for an outside fire. It’s surprisingly common for people to randomly burn trash without a permit. When we arrived, there were 40-foot flames coming from behind the house. The home’s contents had been emptied into the backyard and set on fire. When I pulled a hose around the back, I saw a flash from the tree line and next thing I knew a naked guy was running at me with a machete. Luckily, I can run fast. Should the fire department not respond to outside fires because there might be someone waiting to hack you to pieces?

EMS call is actually someone planning to shoot responders. This happened to the engine crew at my station. They responded to the neighboring district for a medical call. This was back when each station had a different paint scheme on the apparatus. When they arrived, the homeowner looked confused to see black and red fire trucks because the closest station was white and yellow. It turns out his mother had died recently, and he blamed the first responders for her death. He had a gun and made a fake EMS call with the plan to ambush them. Should EMS units not respond to 911 calls because someone might be planning to shoot them?

EMS call turns into a shooting. I was on a single EMS unit that responded to chest pains in a garden apartment. While we were inside assessing the patient, there was a boom outside which turned out to be a shooting on the front steps of the apartment. There was a crowd screaming for help, so we ran downstairs. Unfortunately, a teen had been shot point blank with a shotgun and it was not a survivable injury. If rapid treatment would have helped a kid, I'm not going to hide in the apartment until police say it's safe to come downstairs. When someone needs immediate treatment and transport, should EMS help or wait for police?

Treating victims, putting out fires, and dealing with dangerous situations is your job in public safety.

This is why police and firefighters get paid more than teachers. Obsessing over the ‘what ifs’ of emergencies makes it impossible to do an inherently hazardous and uncertain job.

Why do fire and EMS units stage away from the scene of a school shooting when there are victims inside who need immediate treatment and transport?

In a tragic recent school shooting, a teacher and student were shot with an AR-15 rifle inside CVPA High in St. Louis. They were still alive when police killed the shooter, yet EMS waited 20 minutes until police gave the all clear. Teacher Jean Kuczka and 15-year-old student Alexzandria Bell both died waiting for help inside. With military style rifles being used by school shooters, a campus is like a battlefield where “the majority of combat casualties die within ten minutes of the trauma” (PubMed: Wounded in action: The platinum ten minutes and the golden hour).

A fatally flawed planning assumption during school shooting responses is that medical providers need to stay away until police clear the scene. This makes no sense when gunshot victims need immediate transport to a hospital.

Ann Perkins, a teacher at Santa Fe High, was bleeding to death from gunshot wounds to her legs as police ran past her and EMTs staged away from the school. She called her husband who drove to the campus to save her. She recounts her experience at 8:00 in this documentary on this attack where 23 people were shot two months after Parkland.

There is a saying in the fire service that “you risk a lot when you can save a lot”. This is why firefighters enter a burning building or stand under a broken utility pole to save trapped victims. These are extremely hazardous situations that claim the lives of dozens of firefighters each year (less as equipment and training has improved).

If there is an opportunity to save a kindergartner who is about to bleed out, I don’t think there are very many firefighters and EMTs who wouldn’t be willing to risk their lives to save a child. That’s the job.

Rarely a Second Shooter

I have a couple more questions for first responders:

On a house fire with people trapped, do half of the units stage outside in case there is a second house fire that starts across the street? (Note: a modern data-driven approach is there should not even be a “2 out” crew on a house fire)

Do you dispatch police to chest pains and other medical calls to clear the house before EMS enters because there is a chance that someone is hiding inside a closet with a gun?

Would you dispatch 2 medic units to chest pains because a second person in the house might get overwhelmed by the situation and have a heart attack too?

The answer to all these questions is no because it would be a waste of scarce resources on 99.99% of calls. Being a first responder means that you deal with the emergency in front of you while keeping in mind that some unlikely complication might happen that increases risk.

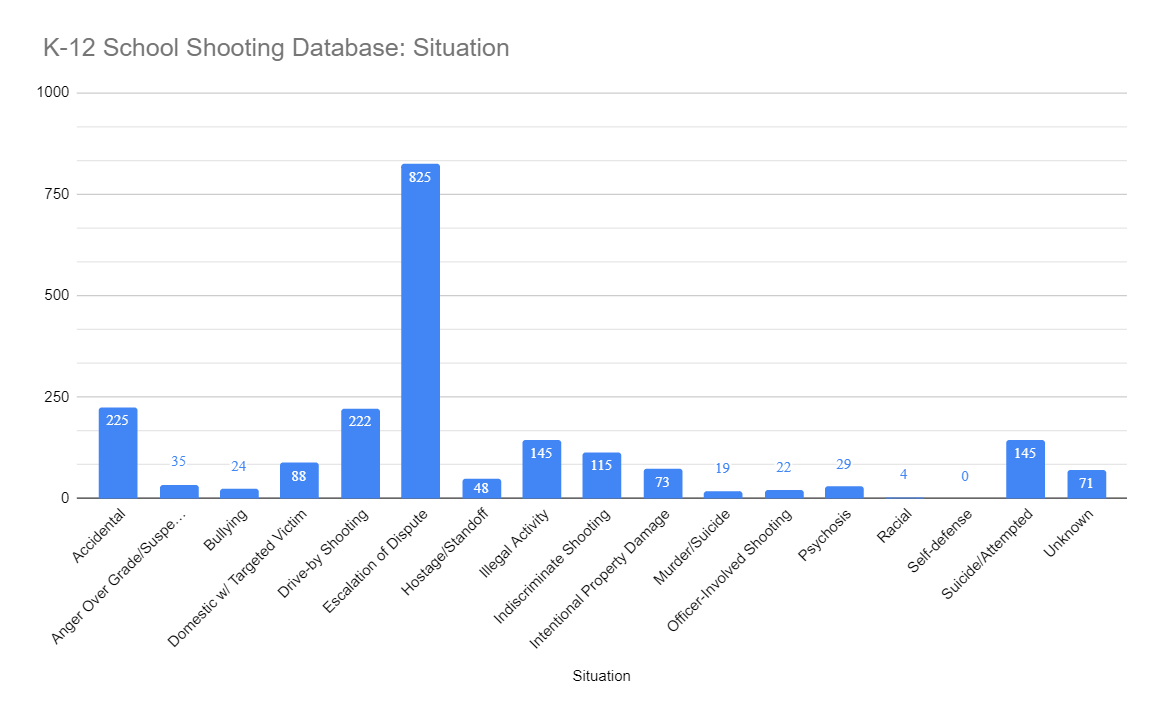

Since 1966, 7 out of 230 planned attacks at schools had two shooters. None involved a second shooter waiting to surprise emergency responders. In 4 of 7 two shooter attacks, they were either subdued, surrendered, or fled before police arrived. During two attacks—Cokeville, WY hostage crisis and Columbine—police waited outside until the attackers committed suicide inside the school. In 1988 at West End Christian Elementary School, two heavily armed men took 84 students hostage for 12 hours before they surrendered to police.

Since “everything changed after Columbine”, there has never been a complex coordinated school shooting carried out with multiple attackers targeting first responders. Meanwhile, there have been hundreds of school shootings since 1999 when wounded children and staff inside needed immediate medical care.

Allowing students and teachers to bleed to death while police search for a second shooter is a planning fallacy.

Why is a second shooter rare?

School shootings and public mass shootings are usually motivated by highly personal grievances. What are the chances that two people have experienced the same trauma and internalized it in the same way that leads them to plot mass violence?

During the 7 multiple shooter attacks at schools since 1966, one involved four armed students with handguns and an AK-47 who planned an attack on rival gang members inside the school gym during a pep rally. Aside from the car bombs that failed to detonate at Columbine and shots fired at police during the Cokeville hostage standoff, none of these attacks have included a plan to target first responders.

When thinking about treating victims, there have been about 10x more victims wounded and killed during single shooter attacks at schools compared to multiple shooter attacks. These charts only show the 230 deliberately planned attacks at schools since 1966 and exclude the more common spontaneous gun violence stemming from fights that escalate.

Unlike terrorists who have shared group beliefs, most school shooters lack clear ideology. When school shootings are violent public suicides, group suicides are rare. It’s been almost three decade since the mass suicide at Rancho Santa Fe which involved group indoctrination and shared cult ideology.

If there is a plot involving two or more students—or a student and an adult plotting an attack together like in Ohio earlier this year—the plan is more likely to be detected because of ongoing communication and planning.

In another example, police were able to stop a two-shooter Columbine copycat plot in Florida because other students overheard them talking about their plans.

Flawed procedures have bad outcomes for citizens

I've experienced the fatally flawed policy of waiting for police to announce that the ‘scene is secure’.

I was in the backseat of the engine for a shooting call where a taxi driver was shot during a robbery. Following protocols, we staged down the street waiting for police to secure the scene. I flipped to the police radio channel, and they were searching for the suspect in a neighborhood a mile away. (Note: after a robbery, the shooter rarely stays at the scene of the crime meaning that the exact location of the shooting is probably the SAFEST place to be).

The 'by the books' Captain on the engine wouldn't do anything until police gave the all clear despite radio traffic clearly indicating the shooter had fled. Police were focused on finding the armed suspect so about 10 minutes passed before they remembered to call-in that the scene was secure. By the time that information was finally relayed across the fire radio channel, the taxi driver was dead. He had a torso wound that was probably survivable if he got treated and transported 10 minutes earlier. The shooter was a mile from the scene so we would be in ZERO danger treating the victim. Instead of recognizing the importance of the US Army’s “platinum 10 minutes”, the policy put responder safety ahead of lifesaving.

This same scenario plays out with wounded children and teachers at a school when EMS units wait outside for police to give an all clear.

Recommendation for updated EMS response policy

The most common circumstance for a shooting at a school is a fight that has escalated into a shooting. During this spontaneous gun violence, the shooter usually flees immediately meaning there is no danger inside. There has NEVER been a shooter who fired at police, EMS, or started firing at random victims after a fight escalated.

Regardless of the situation being a fight, accident, or a planned attack, students who are shot need immediate medical treatment. Based on my data from 60 years of shootings at schools and the US Military’s emergency medical plan, I believe that these procedures should be adopted by all emergency services agencies.

Police

Enter the school immediately.

If there is the sound of gunfire, go towards that gunfire and find the shooter.

If an officer encounters a critically wounded victim and cannot see the shooter, the officer should provide rapid treatment (e.g., tourniquet, trauma dressing, or chest seal) because victims can bleed out within seconds. When an officer doesn’t know the location of the shooter, they should never bypass a victim to search for a assailant who may have already committed suicide, been subdued, or fled.

If an officer does not hear gunshots, they should immediately carry/drag the wounded victim to the closest exit.

Arriving officers should not park police cars in a way that blocks EMS units from arriving or leaving the school. If possible, park in the grass. (note: parking never gets practiced during ‘active shooter’ training because officers are already at the school when the scenarios start).

If an officer is with a critically wounded victim and there is not an EMS unit on scene, the officer should put the victim into a police car and drive to the closest hospital (police at the Aurora movie theater shooting saved victims by driving them directly to the hospital).

Fire/EMS

Park as close to the school as possible so that officers evacuating victims can easily carry victims directly to the EMS units.

If EMS units do not see police officers waiting with victims and do not hear gunshots, they should enter the school wearing high visibility EMS traffic vests and search for victims.

Fire units should park in the grass and not block access to the school (note: fire departments practice parking all the time during training).

Fire personnel should put on turnout gear and high visibility traffic vests then take EMS bags, stokes baskets, and forceable entry tools to the doors of the building.

If fire personnel don’t hear gunshots, they should enter the school and start searching for victims.

If there are more patients than ambulances, fire personnel should get in the back of a police car with a victim to provide medical treatment during rapid transport to the closest hospital.

Note 1: Highest chance of saving lives comes from getting patients rapidly to a hospital instead of keeping victims in a triage area at the scene. See: How One Las Vegas Emergency Department Saved Hundreds of Lives After the Worst Mass Shooting in U.S. History.

Note 2: Concept of a ‘rescue task force’ with police and specially trained medics wearing helmets and body armor has very little lifesaving potential for victims because by the time the task force personnel are assembled, the Platinum 10 Minutes when most battlefield traumas will die is already over.

Teachers/Students/Staff

If you hear gunshots, get out of the building by any means possible.

If you don’t hear gunshots and there is a wounded victim, Stop the Bleed and carry/drag the victim to the closest exit.

Once students are outside the school, they should leave the campus and go to a pre-determined meeting point off campus (e.g., neighbor’s house, church, community center) that their parents plan for ahead of time.

This might seem radical to any first responders who have attended active shooter training for the last 20 years, but we need to remember that the post-Columbine ‘active shooter’ policy and training was invented based on imagination instead of empirical evidence.

If we learned anything from Iraq and Afghanistan (plus the Pulse Nightclub, Vegas, Aurora Theater, etc.), it’s that gunshot victims need rapid treatment and transport. To save lives, the US Military shifted medical strategies in the Middle East to place field hospitals and forward surgical teams in active combat zones. This increased risk to medical providers was worth the benefits of rapid treatment for critically wounded soldiers.

"We used to talk about getting care to a patient in the 'golden hour,' the first hour after injury. Now we are focused on the 'platinum 10 minutes,' when the combat medic provides immediate lifesaving care." - US Army Combat Medicine

If you want to save a life, get a victim moving towards a hospital within seconds. When EMS waits for 20 minutes outside the school (30 minutes total after the victims were shot), this means that a student or teacher may die when there was an opportunity to save them.

Kids Face Real Dangers

Children go to school despite the very real danger that there will be a shooting on a campus somewhere in the US almost every day. When a kid is shot at school, they need to know that an adult will come to their aid, not wait outside for 20 minutes just because their policy book says to. When educators like Jean Kuczka in St. Louis and Principal Dan Marburger in Perry, IA take extreme risks by using their bodies to shield students from bullets, EMS personnel also need to take risks to try to save them.

In the 20 years since Columbine, school shootings have had an increasing number of victims with a higher fatality rate which means the current response paradigm is not working.

When first responders swear an oath to protect the public, we need to put the public back in public safety. If a student is in peril, adults who wear badges and uniforms—police, fire, and EMS—all need to risk their lives to save an innocent child. If a responder is killed taking that risk, there will be a huge funeral and lifetime benefits for their family to honor their sacrifice.

There is no greater honor for a public servant than dying trying to save a child. Public safety is about keeping the public safe and sometimes first responders must put themselves in peril to do that. The consequence of maintaining the status quo that puts the safety of responders above lifesaving is another teacher or student bleeding to death inside their classroom.

David Riedman is the creator of the K-12 School Shooting Database, Chief Data Officer at a global risk management firm, and a tenure-track professor. Listen to my recent interviews on Freakonomics Radio, New England Journal of Medicine, and my article on CNN about AI and school security.

David,

As a career Paramedic and Firefighter for many (30+) years, I appreciate the time and effort you took to address these issues. As you know, in the past empirical evidence was rarely used in the development of policy, procedures and protocols for EMS systems. It still is the exception and not the rule. In the past I have shared your information with my former SWAT supervisor (now in a leadership position within a large police department) and will share todays article with a EMS Division Chief within a large Fire based EMS System.

Tom