“One Second From Columbine”: Connecting the Dots Before School Shootings

More than two decades later, each 9/11 anniversary continues to be a stark reminder of everything that went wrong leading up to that…

More than two decades later, each 9/11 anniversary continues to be a stark reminder of everything that went wrong leading up to that fateful day. Elected officials underestimated the threat. Intelligence agencies weren’t communicating or sharing information. Witnesses to the warning signs had no means to report them. First responders didn’t have the equipment they needed. As the 9/11 Commission concluded, the Pentagon, CIA, and FBI “failed to connect the dots”. These same themes echo in the Texas House Committee report on the failures at Robb Elementary in Uvalde.

The fall before Uvalde, as the country laid wreaths and swore never to forget 9/11, two Florida teenagers plotted a “Columbine style” massacre in Lehigh Acres. The teens studied the Columbine blueprint and shootings like it to calculate how best to terrorize their victims and achieve the most casualties. They mapped out the gas lines at school to plant pipe bombs near them, and marked security cameras to avoid detection. They held planning meetings on Zoom and recruited other students to join their scheme. Had it not been for a substitute teacher sounding the alarm, last school year would have opened with yet another massacre at an American school.

Columbine claimed the lives of 12 students and one teacher in Littleton, Colorado, just 18 months before the Twin Towers fell. And like 9/11, there were too many warning signs to ignore — ominous threats, prior arrests, detailed plans, videotaped confessions. So how is it that 21 years removed from 9/11 and Columbine, the prospect of yet another preventable tragedy this school year looms so large? How is it that these same warning signs continued to be missed in Oxford, MI and Uvalde, TX?

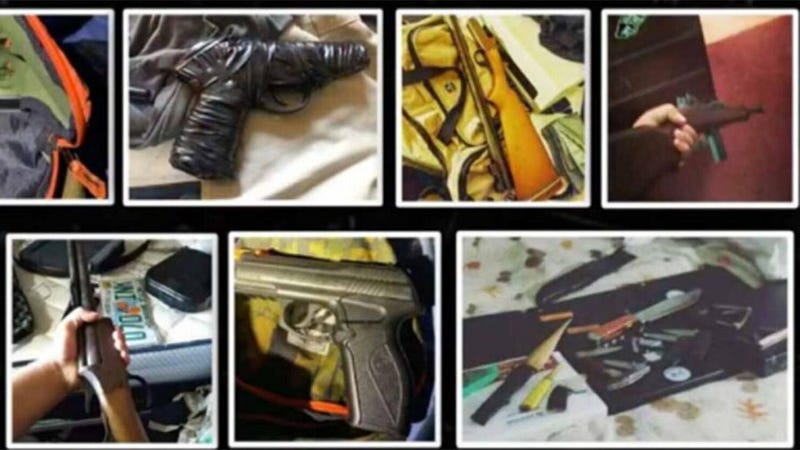

Before the Florida teens were arrested last year, other students knew about the planned attack. They were so scared about it they started running out of the classroom when one of the plotters reached into his backpack. The teens’ parents, and local police, knew there was a problem too — officers had been called to their homes more than 80 times. The teens, both too young to purchase guns and ammo, had a stash of weapons in their bedroom. One posted photos with the guns on Instagram while posing in front of a confederate flag. Just months later, teenage school shooters in Michigan and Texas posted similar photos prior to their attacks. Those overt warnings were also missed.

The Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Act was passed in Florida after a comparable system failure when a former student murdered 17 students and injured 17 more in Parkland in 2018. The Act created a state office for school safety, threat assessment training for school officials, funding for school police officers, mandatory reporting, and zero tolerance policies so strict that even elementary school children end up in handcuffs.

Not one of these new resources averted the Lehigh Acres shooting. Instead, it was a substitute teacher who spoke up when a gun was already in the school. This eleventh-hour aversion was yet another glaring failure to “connect the dots”. Either students, teachers, parents, and anyone else who saw the teens’ threatening online posts didn’t report the warning signs, or law enforcement didn’t take them seriously. Clearly, police and school officials were not communicating if officers went to their homes 80 times, yet a handgun still ended up in a classroom.

This is not just a Florida problem. One of the teen perpetrators of the 2018 Denver STEM School shooting, just miles from Columbine, was sentenced Friday to life in prison without parole for killing one student and wounding 8 others because the same warning signs were missed there too. The lights were flashing red before Robb Elementary and Oxford High. When a freshman at Embry-Riddle University in Daytona Beach, FL failed out of classes, sold his car to get the money to buy a rifle, and gave away his belongings, the school’s threat assessment team failed to notice these obvious red flags. Another massacre was averted by a classmate who saw a social media post at 3 AM — just hours before the attack — and called campus police. He was arrested with a rifle and 6 magazines on his way to campus.

These narrowly averted attacks were not successes, they were failures of the threat assessment system designed to detect them long before a student approaches the campus with a rifle and a plan to kill their classmates.

Thousands of other school shooting threats have been reported across the country during the last school year. They range from jokes to narrowly averted attacks. A Miramar, FL student posted threats online and was arrested while walking across the campus with a gun. Two Chicago students talked about a shooting, one brought a gun, the other brought ammo to the school. A Louisiana student made threats online and was arrested with a handgun and extended magazine when he arrived at a school.

Guns have been fired on K-12 school campuses more than 250 times since August 2021 in 46 different states. To put that in perspective, there have been fewer than 60 shootings each year between 1970 and 2017. 2021 broke all of the records and 2022 is already on pace to be worse with an average of one shooting per school day.

Students and teachers must feel safe to report threats. Schools need crisis response team protocols that encourage school leaders to break down codes of silence and collaborate with community partners. Schools also need viable alternatives to arrest, so students planning violence receive holistic intervention such as suicide prevention or social services.

In states like Florida with permissive gun laws, safe storage of firearms is paramount because teens almost always get guns from parents. Red flag laws which enable the temporary removal of firearms from homes at times of crisis can also help reduce the prevalence of these attacks.

Teenagers shouldn’t die in their classrooms, or wind up in prison cells for their entire lives. There are better ways to stop violent tragedies before they happen. We cannot wait another 20 years for this message to resonate and real change to occur.

David Riedman is the co-creator of the K-12 School Shooting Database and a Ph.D. student at the University of Central Florida. To support the K-12 School Shooting Database and The Violence Project, please donate.

Note: This is an updated version of the article “ Riedman, D., Densley, J., & Peterson, J. (2021, Sept. 24). One second from Columbine at Lehigh Acres. Sun-Sentinel.”