When is a school shooting threat real?

Schools across the country deal with thousands of online threats every month. Are these real threats of violence, empty threats intended to disrupt classes, or just bad jokes made by kids?

I’ve been trying to better understand how to assess school shooting threats for the last five years. Last spring, I wrote a four-part series about “noise” in the threat assessment process. My PhD dissertation is about reducing this noise (variability) by evaluating threats with AI Large Language Models like ChatGPT instead of humans.

Over the last few years, I’ve also written about the cyclical nature of these threats and how to spot errors when school systems report them.

School shootings come at the end of a long chain of failures. The biggest reason we continuously fail to either take a real threat seriously or dismiss an empty threat is that we don’t and can’t know which one is truly dangerous.

Why is it so difficult to know if a student intends to commit violence when they post a school shooting meme online? I was listening to my favorite astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson explain Schrödinger's Cat and I realize this theory is the heart of the problem.

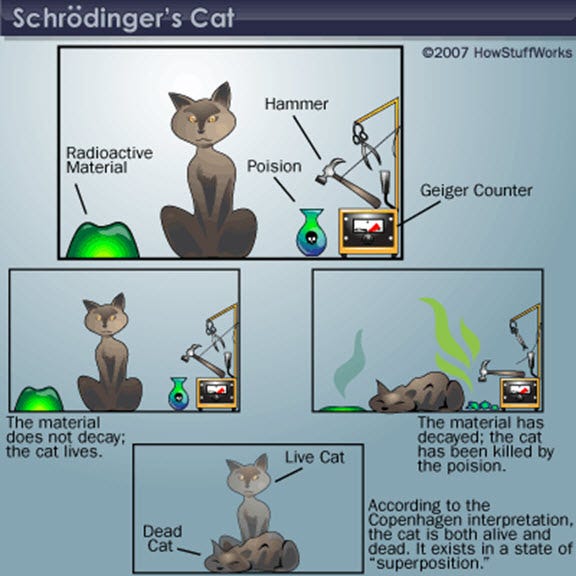

Schrödinger's cat is a thought experiment where a cat is placed in a sealed box with a radioactive atom, a Geiger counter, a vial of poison, and a hammer.

If the atom decays, the Geiger counter triggers the hammer to break the vial, killing the cat.

If the atom doesn’t decay, the cat remains alive.

The quantum mechanics theory based on this is that until the box is opened, the atom is simultaneously decayed and not decayed, meaning the cat is both alive and dead at the same time. This paradox highlights the problem of measurement in quantum theory, where the act of observation collapses the superposition into one definite state.

Before a school shooting threat assessment process starts, a threat made online exists in a state of ontological ambiguity. The state of the threat isn’t unknown. The problem is that the binary categories of real and hoax have no fixed meaning yet. This is a superposed epistemic state, where all possible realities coexist as potentialities. Each threat starts by existing as both a real danger and a hoax at the same time.

Schrödinger’s cat is not a cat with an unknown fate, the cat is either dead and alive. Each school shooting threat is also both credible and not credible, because no act of measurement has yet imposed a binary resolution on a fundamentally indeterminate situation.

This paradox deepens because once school officials or police start to investigate, the original state of the threat ceases to exist. During a police interview, the student who made the threat may reshape their own narrative by saying they only made the statement as a joke, even if they originally planned to commit violence. Alternately, a student who was actually joking might make a false confession under the pressure of police. A police officer who wants to make an example of a student may add their own interpretation of the severity of the threat into the official documentation. The act of the investigation extends beyond the “observer effect” in social science. It becomes observer entanglement because the observer becomes part of the system they are studying.

Because of ontological ambiguity and observer entanglement, a school threat never had a fixed essence. Its “truth” is retroactively constructed by the process of interpretation and judgment which leave the original outcome (real intent to commit violence or not) infinitely unknowable.

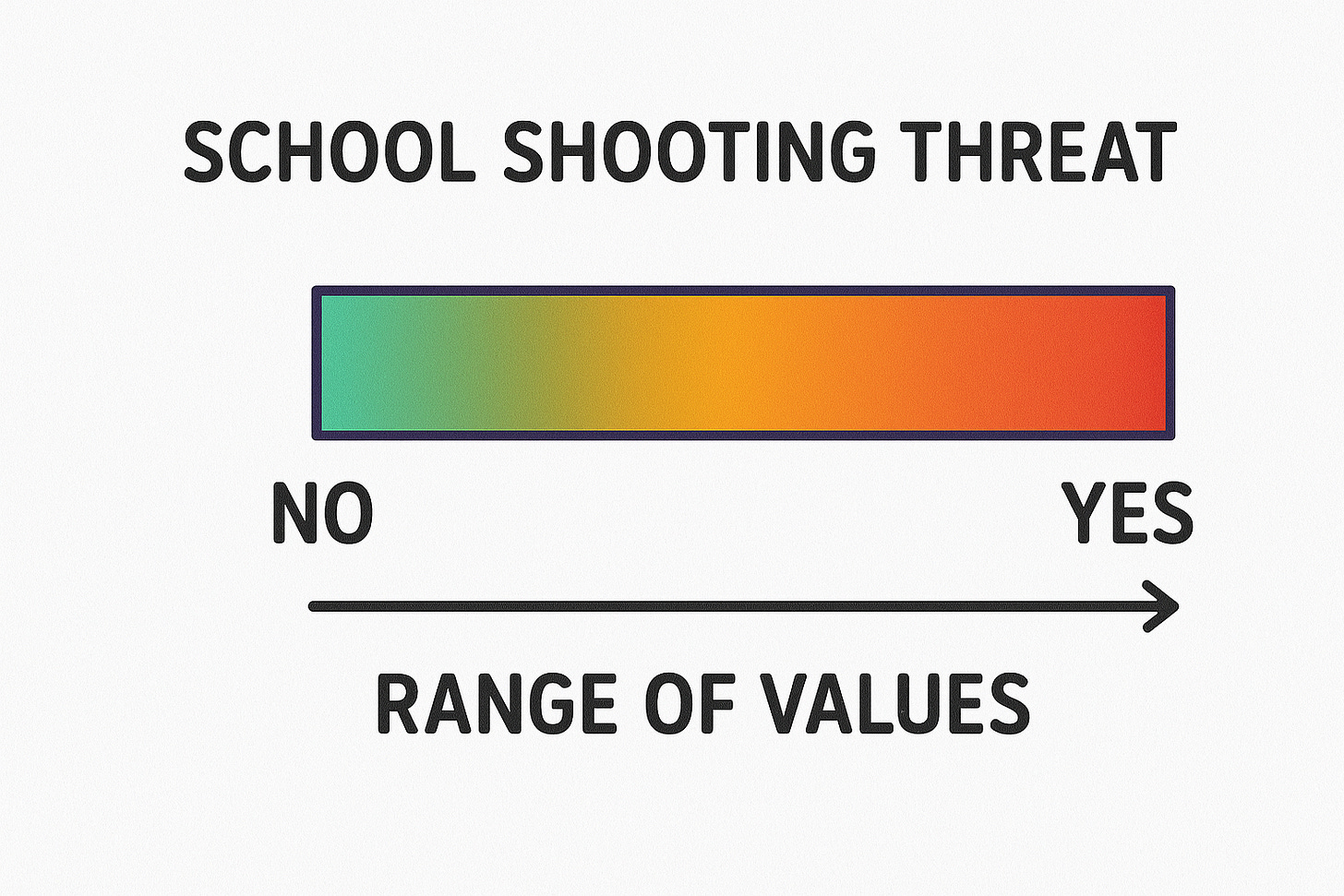

School shooting threats are the Schrödinger's Cat paradox because every threat is both a valid threat and not a valid threat. When threats are not actual acts of violence, the absence of actions is not the counterfactual to the validity of a threat. There is no right answer because both possibilities are both true and false. This means the only way to evaluate these threats is with a range of values based on probabilities instead of a binary assessment like real threat vs. hoax.

Quantum Uncertainty

Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle states that you cannot know both the position and speed of a subatomic particle with perfect accuracy at the same time. This is because the measurement of position of the particle impacts the momentum and measuring momentum changes the position. The more precisely you know one, the less precisely you can know the other.

The biggest flaw in thinking about school shooting threats as a binary of either real threat or hoax is that the act of making a threat and the process of assessing the threat is not a game with fixed rules and outcomes. It’s a process that exists exclusively in a state of uncertainty.

In a game—chess, football, or Call of Duty—success is measurable because the parameters are clear. The rules are established, the players and moves are clearly defined, and the end state (like checkmate, scoring a goal, or winning/losing) is observable and agreed upon by everyone involved. This predictability allows us to measure success objectively.

Inversely, a school shooting threat is nothing like a game. The “rules” are constantly changing and unknowable. A threat can come in any form from a tweet to a group chat meme to a drawing on a bathroom wall. The players involved—usually students—may not even fully understand their own intentions when making a threat. The timeline between a threat and possible violence is nonlinear. A threat might be made minutes, hours, days, months, never, or only be discovered after a school shooting already occurred. If a threat is discovered before violence has happened, the outcome is fundamentally unknowable because the very process of investigating the threat alters its nature.

Because of this uncertainty, we can’t “win” or “lose” when it comes to school threat assessment. This is because every intervention reshapes what might have happened and we will never know whether this changed the outcome.

Science requires counterfactuals

If police intervene after discovering a school shooting threat online and the student doesn’t commit violence, was the threat never real because a school shooting didn’t happen? Or did the intervention successfully prevent it? The truth is, we can’t know.

The reason lies in the absence of a counterfactual when we can’t replay the exact same scenario without intervention to observe what might have happened. The details from interviews can’t determine this because even the students themselves might not fully understand their original intent. After the fact, their own narrative may change or be reshaped by the investigation. Maybe a student posted a violent meme because they were on a pathway to committing violence but once the student tells police the meme was a joke, the student actually changes their mind and abandons their plot.

Inversely, if a student in crisis was crying for help by posting a violent meme and it’s dismissed as a joke after they are interviewed by police, this might push them further down the pathway to committing a school shooting (this happened before the attack at Apalachee High in Georgia last year).

This might sound like a bunch of theoretical nonsense but it highlights the nature of why threat assessment is so difficult. The more successful a threat assessment is in preventing an act, the more it erases the evidence of what it might have prevented. This creates a paradox because the more effective our prevention methods appear to be, the less we can empirically prove they actually worked.

Threats are not linear and binary

Traditional evaluation methods in science depend on stable, binary categories (threat is real or not) but this approach doesn’t work in a situation defined by quantum uncertainty.

A threat can begin as a joke but turn serious under scrutiny. Conversely, a real plan may dissolve into denial, or the student decides to stop plotting once it’s discovered. Because the outcome (a lack of violence occurring) can only be attributed retroactively, the success of the assessment system isn’t knowable because the original state has been fundamentally altered by the very act of investigating.

This means that when no violent incident occurs, it’s often assumed that the threat was successfully averted. But when an act of violence does happen, it’s assumed that the assessment failed even if the warning signs were ambiguous. Since there’s no fixed outcome to measure, this makes the effectiveness of threat assessments less about empirical validation and more about crafting a post hoc story based on hindsight.

Dealing with the paradox

In Schrödinger’s paradox, a cat inside a sealed box is both alive and dead until the box is opened because until that point, the quantum state that determines the cat’s fate exists in superposition. Before a school threat is investigated, it also exists in that same state of ontological ambiguity. It is not simply unknown whether the threat is real or a hoax because those categories do not yet apply. The threat is both real and not real at the same time.

This leads us to a hard truth: there is no “correct” answer. Each threat exists as both valid and invalid. Each student is both dangerous and not dangerous. Every possible attack is both violence that needs to be averted and harmless.

Because every investigation changes what might have happened, there is never a counterfactual (control group) and no way to know what the original outcome would have been. This makes scientific validation of threat assessment nearly impossible.

Instead of seeking binary judgments, we must assess each threat as a range of probabilities based on severity, intent, and risk. Just as quantum physics tells us that we can’t know both the exact position and speed of a particle, we can’t know both the true intent of a student and the outcome of their actions.

Investigating a threat means that we will never know if something bad was going to happen without intervention. The better (or worse) we are at prevention, the less empirical proof we have that we prevented anything at all.

David Riedman is the creator of the K-12 School Shooting Database, Chief Data Officer at a global risk management firm, and a tenure-track professor. Listen to my weekly podcast—Back to School Shootings—or my recent interviews on Freakonomics Radio, New England Journal of Medicine, and my article on CNN about AI and school security.