Using 'first principles' thinking to decrease school shootings by 10x

Silicon Valley innovators breakdown complex problems into fundamental truths, identify current assumptions, challenge the status quo, and create completely new solutions.

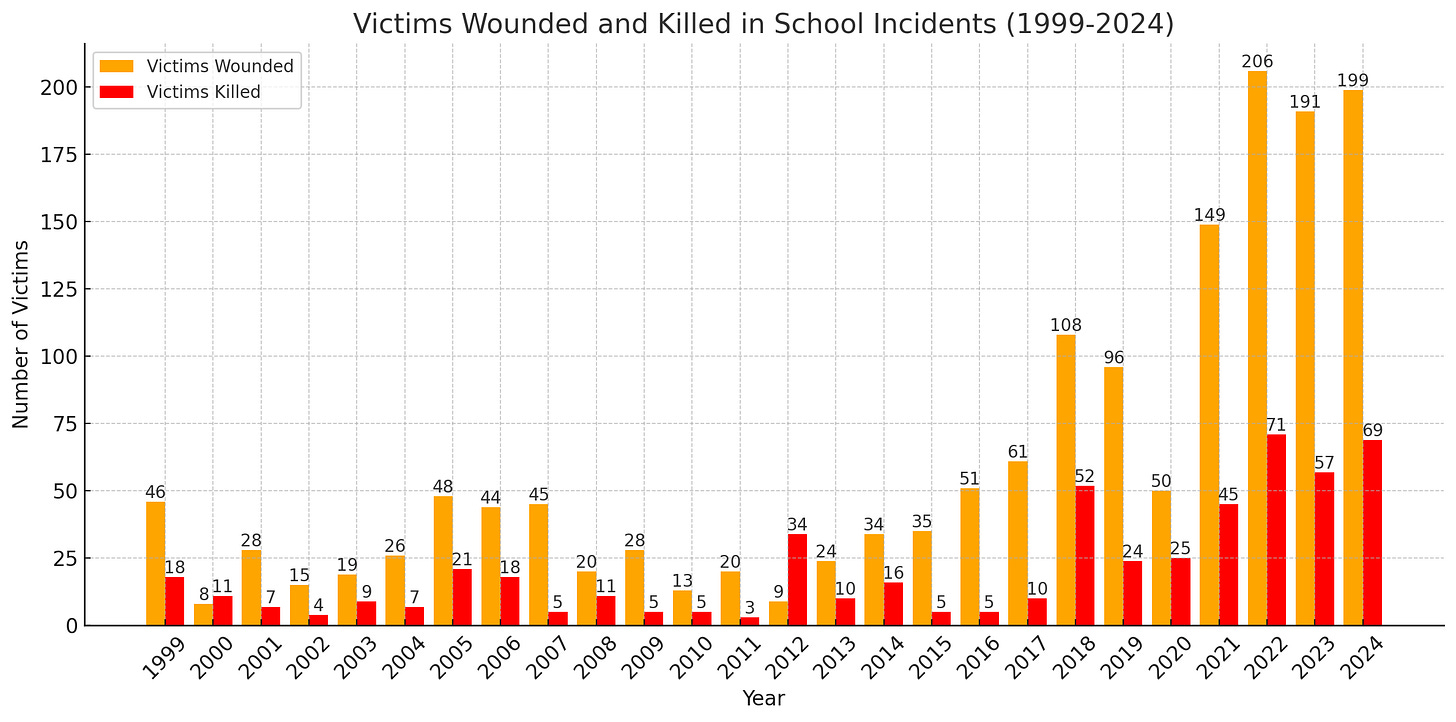

There have been at least 300 shootings on school campuses each of the last 3 years. 2024 was a 5% reduction from 2023 but the total was still 10x higher than a decade ago. When these numbers represent bullets flying down school hallways and kids’ lives, what can we do to reduce this problem by 10x?

If you want to make ~$3M per year in profits, you can buy and run a hotel. If you are really clever with branding and marketing, maybe you can make $8M instead of $3M by tweaking some aspects of the business.

If you want to make $8 BILLION instead of $8 million, you challenge the basic assumption that guests stay in a hotel, and you create a website to rent empty houses and apartments to travelers. This is how AirBNB used a concept called ‘first principles’ thinking to upend the norms in the long-established travel industry. The basic concepts of this process are:

Break down problems into their simplest elements

Identify current assumptions

Challenge the assumptions and avoid analogous thinking

Create new solutions from scratch

The current school security enterprise is driven by maintaining the status quo, repurposing ideas (e.g., castle-style fortified designs, hot spot policing, TSA-style screening, Secret Service model for identifying assassins targeting the President), and making little tweaks to existing programs for marginal gains at schools.

If we want to reduce the number of people shot on campus from 250 to 25, we need to use first principles to figure out the foundation of these problems and come up with completely new solutions. Putting another police officer on campus, an electronic lock on the front door, or sending the school administrators to a 3-day threat assessment workshop is just continuing business as usual with another chain hotel.

More About First Principles

First principles thinking is a foundational problem-solving approach embraced by the most successful Silicon Valley billionaires. It involves breaking down complex problems into their most basic, fundamental truths and reasoning up from there. This approach enables innovative solutions by challenging the status quo and encouraging fresh perspectives.

Breaking Down Problems: Instead of starting with existing solutions or frameworks, first principles thinkers deconstruct problems into their simplest components. For example, Elon Musk applied first principles at Tesla by analyzing the raw material costs and building a new type of battery instead of accepting the market price for the previous generation of low performance batteries.

Identify Current Assumptions: Many companies iterate on existing ideas (e.g., making a product slightly better). First principles thinking seeks to question whether existing solutions address the fundamental problem. As I explained in the intro, Airbnb disrupted the hotel industry by asking: “What’s the fundamental purpose of a place to stay?” rather than improving traditional hotel models.

Challenging Assumptions: Innovators question why things are done a certain way and explore if those methods can be reimagined. SpaceX reimagined rocket design by questioning the basic assumption since the first fireworks were invented in China centuries ago that rockets must be single-use. Reusable rocket technology changes everything because it’s so much cheaper and allows for a higher volume of launches.

Creating New Solutions from Scratch: By focusing on core, foundational components of a problem, entrepreneurs can innovate in directions that challenge the status quo of an established industry. It was taken for granted that product manufactures use third party companies for logistics and shipping. Amazon developed its own fulfillment and delivery systems instead of relying on third-party solutions which significantly reduced costs, improved scalability, and created one of the biggest companies in the history of humanity.

What’s the equivalent to using first principles to land a 11,000,000 pound rocket—which everyone assumed was impossible so they didn’t even try—when it comes to preventing gun violence on campus?

Break Down Problems into their Simplest Elements

The core problem for school safety is how do we prevent people—students, staff, and community members—from being shot on school campuses?

The three most foundational elements are:

Someone is motivated to cause harm.

That person can access a gun.

A school campus is an open and accessible public place that people use every day.

If someone—usually a student—is motivated to cause harm and can get a gun, it’s easy for them to take the gun to a school.

From a first-principles standpoint, you can think of a school shooting as the combination of these elements. If any of the three is disrupted—(1) the individual’s motivation toward violence is changed, (2) access to firearms is significantly constrained, or (3) the open-school environment is restructured—the likelihood of a school shooting happening decreases dramatically.

Identify the Current Assumptions

Tweaking the status quo at schools might reduce the problem by 5-10%. Just look at policing and crime rates since we started recording crime data in the 1930s. We have collectively spent trillions of dollars on policing just to have small dips in the overall rate of crime. Following conventional thinking, assigning more officers to a school campus—known as ‘hot spot policing’—is an expensive, intrusive, and generally ineffective way to maybe get a small reduction in gun violence rates.

Completely eliminating a problem like school shootings requires a clean sheet of paper which is a radical change. Here are seven assumptions that have become the status quo for school security:

Conventional Thinking Assumption 1: More police and armed security is the best way to prevent shootings.

Conventional Thinking Assumption 2: Fortified buildings will keep a school shooter out and protect the kids inside.

Conventional Thinking Assumption 3: School shooters always show clear warning signs.

Conventional Thinking Assumption 4: Schools need to be big campuses that students attend for multiple years on the same schedule every week (e.g., classes from 8am-3pm on Monday to Friday from September to June).

Conventional Thinking Assumption 5: Gun control laws are politically infeasible so we can’t do anything to regulate firearm storage and access.

Conventional Thinking Assumption 6: Primary responsibility for student safety lies with schools and law enforcement.

Conventional Thinking Assumption 7: If a shooting (or threat of a shooting) happens on campus, a school should go on “lockdown” with students hiding in the closets and corners of classrooms.

Challenge Assumptions and Avoid Analogous Thinking

Instead of asking, “How do we prevent school shootings?”, why don’t we reframe it as:

“How do we eliminate the conditions that allow school shootings to occur?”

This shifts the focus from reacting when it’s already too late to transforming the environment and societal dynamics that make a school shooting possible. This means questioning not just the methods, but the very foundational assumptions underlying school safety, education systems, and social norms. Instead of duplicating old ideas, here's a bold, unconventional framework:

Challenge #1: Stop ‘Hot Spot’ Policing Schools

Conventional approaches typically involve stationing armed officers or security on campuses to deter shooters. In reality, there were police officers or armed security on campus during most of the recent planned attacks and they did not deter or prevent the shooting. Armed security can unintentionally escalate situations, create a more militarized environment that negatively affects school climate, increase risks from accidental shootings and misplaced firearms, and may even make a school a more attractive target for a suicidal student who wants to die during a violent public shooting.

Another issue is the cost of police or school resource officers, particularly on large campuses that require multiple—or dozens—of officers to effectively patrol. Allocating substantial funds for security in a resource constrained school means that less funding goes to mental health services, counseling, reducing class sizes so that troubled students get noticed, or community programs that address the root causes of violence. If a shooting happens on campus, schools—just like any public places— already have access to an emergency police response by calling 911.

Instead of more status quo policing, schools can put this funding into proven violence-prevention strategies like crisis intervention, counseling, and conflict resolution training. By focusing on community building, fostering a positive school culture, and creating supportive services, schools can move away from a surveillance- and punishment-based model toward a more holistic and proactive approach that reduces or eliminates the conditions that create the crisis for a potential school shooter.

Learn more: Ep 28. Why School Police May Not Be the Best Way to Prevent Violence

Challenge #2: Open Campuses Are Safer Than Closed, Fortified Schools

The conventional assumption is to “harden” schools with fences, locked doors, and single points of entry to keep threats out. However, heavily fortified structures can create a false sense of security, especially considering that school shooters are mostly likely to be currents student who are allowed inside the school. To make matters worse, locked and constricted spaces (e.g., secure entry) can trap potential victims, rather than keeping intruders out.

Visible physical security may also increase anxiety among students and staff to inadvertently transform schools into environments that feel more like prisons than learning communities. By contrast, more open campuses—multiple exits, fluid movement across campus, and integration with the surrounding neighborhood—can allow faster evacuations, reduce choke points, and encourage natural oversight and interaction by neighbors, parents, and local businesses.

Redesign strategies can involve cultivating broad visibility, natural surveillance, and multiple safe exits, rather than relying on one heavily guarded front door (e.g., the fortress mentality). Schools might also consider integrating into community centers or shared spaces that bring more adults onto campus rather than keeping the community out. Interactions, informal mentoring, and observations from a larger groups of adults might identify a problem or a student in crisis before they bring a gun to the school.

Learn more: Ep 22: The Fortress Problem is a paradox because defenses create vulnerabilities

Challenge #3: Formal Threat Assessment Teams Are Unlikely to Find Every School Shooter

Many schools create teams of administrators and law enforcement—known as a ‘threat assessment team’—to create a list of students who might be dangerous based on tips and overt warning signs. The problem is that the planning for a school shootings usually occurs in private spaces that can only be accessed by student like encrypted chats or discussions in the back of the school bus. Students may be hesitant to report their peers due to fear of retaliation or sending a classmate to prison. False positives can damage trust and stigmatize a student who was never a threat.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to School Shooting Data Analysis and Reports to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.