The Layered Security Fallacy

345 Park Ave is a high-end commercial high-rise with CCTV, lobby security, and access cards. But layered security (Swiss Cheese Model) only reduces risk if each layer is effective.

The “Swiss Cheese Model” is a common buzzword in facility security.

It started as a risk management framework borrowed from aviation (both pilots check flight plan) and healthcare (disinfect the OR, sterile gowns, clean the skin, and give an IV antibiotic during surgery). Imagine multiple slices of Swiss cheese stacked together, each one representing a layer of risk reduction. Each slice has holes, but if they’re staggered just right, the holes won’t line up, and the threat gets caught somewhere before reaching catastrophe. In theory, it’s brilliant.

345 Park Avenue in New York, NY is a 44-floor skyscraper that’s home to major corporate tenants including Blackstone, KPMG, Bank of America, and the National Football League. This building has “layered security” including CCTV cameras that recorded a man with a rifle approaching, guards in the lobby, visitor parking management, and access control.

While the Swiss Cheese Model seems like a good theory, in practice having multiple ineffective layers don’t give you any real security against the biggest threats. When there is a planned attack by a heavily armed shooter, do layers like CCTV cameras at the entry, guards in the lobby, and printing ID stickers for visitors do anything to prevent mass violence?

These layers didn’t work last night when a man with a rifle double parked outside the building, shot a police officer and guards in the lobby, and then took an elevator upstairs. He was apparently targeting NFL executives (an organization with many layers of security) but he took the elevators to the wrong floor by mistake.

The false security of multiple layers is compounded by a term I coined “The Matrix Problem” when staff at a metal detector or security checkpoint don’t actually think they will find a weapon. When they do encounter an armed person, they are neither prepared, trained, nor equipped to deal with the situation.

Back to the layered security fallacy, let’s run the numbers.

What Does Layered Security Actually Do?

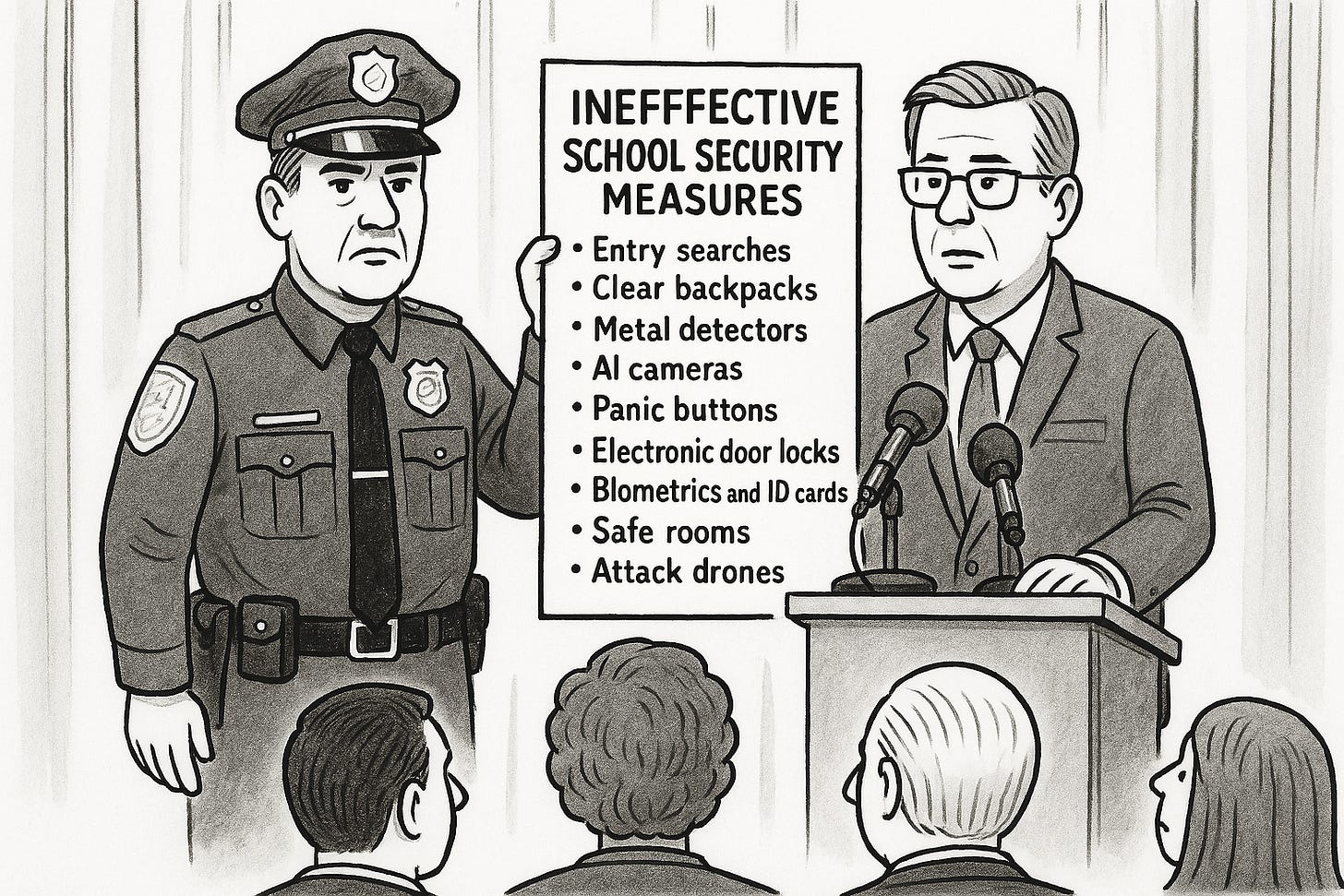

Say you’ve got nine safety measures and each one reduces risk by 1%. Think about some common security systems and practices:

Entry searches: Take a long time, need lots of staff, and have a high error rate if the process is rushed.

Clear bags: Gun can easily be inside a pouch, wrapped in clothing, or inside a book.

Metal detectors: Alarm gets set off by every metallic object (water bottles, phones, keys, laptops).

Lobby security guards: Officers sitting in the same chair every day for hours are rarely going to be ready for the split-second response to an ambush.

Panic buttons: Get triggered by accident and rarely make a difference during an emergency (because everyone has a cellphone).

Electronic door locks: Front doors of high traffic buildings are usually unlocked because it’s not practical to buzz every person in through a locked door. In a commercial building, access control is usually located near the elevators.

Biometrics and ID cards: Most shootings are committed either by people who are allowed to be inside a building and have access cards, or an assailant who enters through the front door with the plan to immediately shoot at the security guards.

Safe rooms: Most planned attacks at schools begin and end inside the same room. Most spontaneous (not preplanned) shootings happen outside and are over in seconds.

Attack drones: Most shootings are over within seconds and how can an attack drone tell the difference between an assailant and police officers, plainclothes officers, security guards, and random people or students holding dark metallic items like cellphones.

While each of these measures won’t do much to prevent a shooting, reducing risk by 1% might sound like it still makes a difference, but math tells a different story.

Assuming that each layer lets through 99% of the risk:

0.99⁹ = 91.35% of the risk still gets through.

Only a 8.65% total risk reduction.

If you stacked a 10th 1% layer:

0.99¹⁰ = 90.44% of the risk still gets through.

Only 9.56% total reduction.

In reality, high tech security like AI cameras and attack drones are more like a .1% risk reduction but still imagine if you had 100 of those layers:

Risk retained per layer = 0.999

Total retained risk after 100 layers = 0.999¹⁰⁰ ≈ 90.48%

This is why the Swiss Cheese Model is such a stupid way to justify ineffective security measures. For comparison, if you have a single strong measure that reduces risk by 90% on its own:

One 90% effective layer = 90% risk reduction.

Three 90% layers? That’s 0.1 × 0.1 × 0.1 = 99.9% reduction.

That’s not theoretical. That’s the math behind why good systems work and why bad systems fail despite being “layered”.

The 90% Layers That Actually Work

What are some potential ways to reduce the risk of mass violence by 90%? We need to remember that like the mass shooting in NYC last night, these planned attacks are violent public suicides that usually end on the shooter’s terms. Luckily, we can use the same evidence-based suicide prevention programs to stop many of them from happening.

In schools these solutions can be:

1. Behavioral Threat Assessment

When a student is on the path to violence, they almost always leave signs. Threat assessment teams of trained professionals who investigate behavioral red flags can intervene before a gun is ever brought to school. When done well, these teams don’t just reduce shootings. They reduce suspensions, racial disparities in discipline, and suicide risk.

2. Relationships with Trusted Adults

If a student feels like they can talk to someone, they’re more likely to share concerns. Students leak plans all the time when they text friends or post cryptic messages online for their classmates to see. If a classmate or friend sees the signs and trusts an adult enough to share this information, many shootings can be prevented. (More threats before an attack correlates with more victims when the attack happens)

3. Rapid Staff Response to Threats

When something happens, every second counts. Lockdown procedures don’t work if teachers hesitate. Evacuations fail if staff are unsure of where to go. The best emergency response is calm and well-trained adults who know what to do during an emergency and get it done.

Think back to Apalachee High in 2024. When the school got a phone call from a student’s mother about an imminent school shooting about to take place, the school staff had no idea what to do. Staff spent time searching for the wrong student because they lacked resources, training for this situation, basic knowledge about enrolled students, or didn’t have systems to figure out where students are on campus.

Being prepared for a worst-case scenario ambush by a gunman in the lobby requires real training, not just annual PowerPoints, panic buttons, and a metal detector wand. Ideally, real risk reduction programs to identify and help someone in crisis before they ever show up with a gun.

Why the Swiss Cheese Model Persists

Here’s the painful truth: weak security layers are easy to sell. They’re easy to explain, easy to budget, and politically safe even if they don’t actually work.

The Swiss Cheese Model assumes the holes won’t line up. But when it comes to facility security, weak slices tend to fail in the same situations like a surprise attack.

It’s not enough to have a bunch of layers. The layers themselves must be meaningful risk reduction.

Skip the Moldy Cheese

When your security strategy includes ten different layers, but none of them really reduce risk, you don’t have any security at all. You just have a collection of useless stuff and some wishful thinking.

Mass shootings in public places and school shootings are rare, but they’re devastating. Prevention doesn't require physically fortifying every building (Ep 22: The Fortress Problem is a paradox because defenses create vulnerabilities) or manually searching every backpack. It requires smart, meaningful, evidence-based strategies that actually make a difference.

If your office, mall, or campus is serious about preventing gun violence, you don’t want ten slices of moldy cheese.

David Riedman is the creator of the K-12 School Shooting Database, Chief Data Officer at a global risk management firm, and a tenure-track professor. Listen to my weekly podcast—Back to School Shootings—or my recent interviews on Freakonomics Radio, New England Journal of Medicine, and my article on CNN about AI and school security.

You are exactly on point, again. The only thing that saved the intended targets was the shooter’s mistake. No amount of security could save the victims.