Most school shooters flee. Why do police search every room of the school?

After shooting five classmates, a student at Wilmer-Hutchins High in Dallas ran from the campus before police arrived. This is the most common outcome during a school shooting.

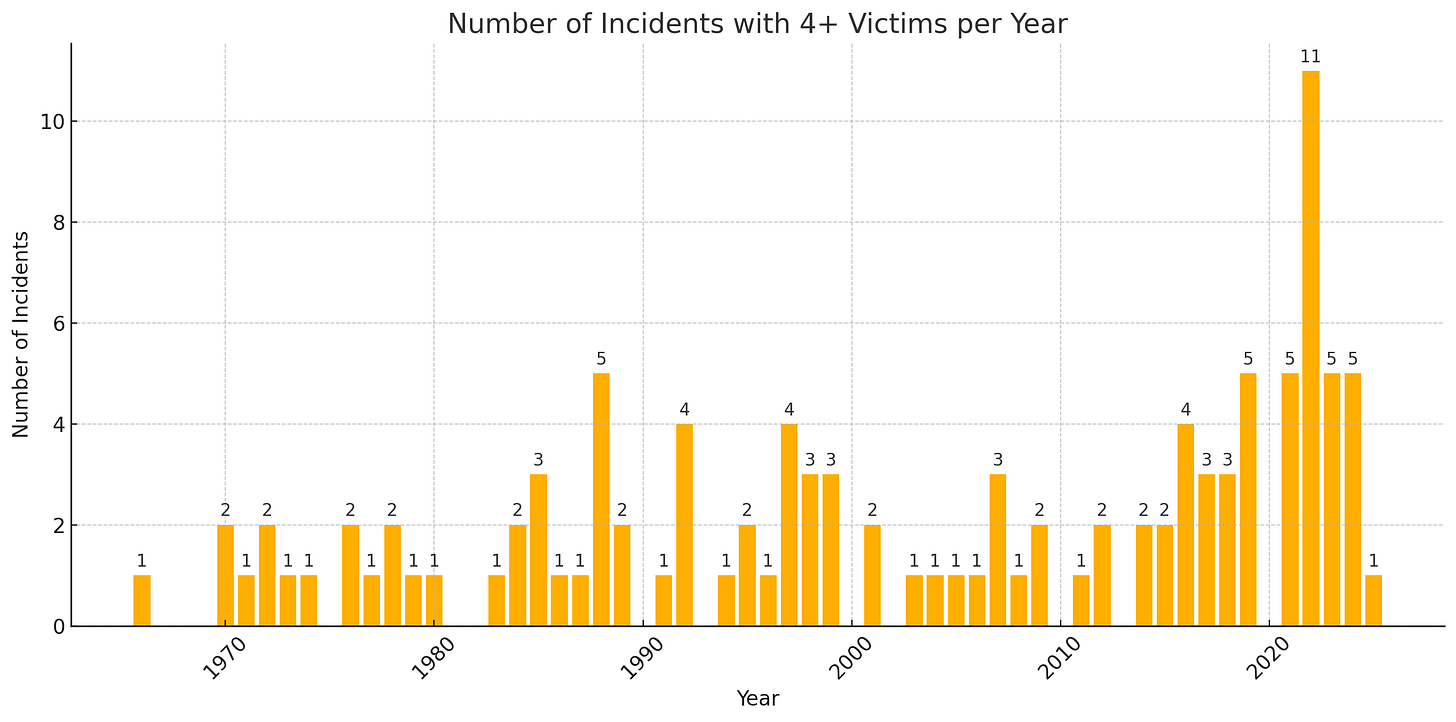

Five students were shot, and another sustained a serious leg injury fleeing when a student opened fire in the hallway of Wilmer-Hutchins High in Dallas on Tuesday afternoon. This is the first “mass shooting” with more than 4 victims at a school in 2025.

Even with metal detectors, clear backpacks, school police, CCTV, emergency alert system, and secure entry, this is the second shooting inside the same school since April 2024.

During a press conference, the police chief said "it was not a failure of our staff, of our protocols, or of the machinery that we have". Here is what we know so far:

17-year-old student snuck a gun through a side door that was opened by another student.

Firearm was a semi-auto handgun with an extended magazine.

Shooting took place in a hallway not a classroom as was initially reported.

Student fired "indiscriminately" in the crowded hallway before standing over an injured student who fell and shot him at pointblank range.

Shooter fled from the scene before police arrived (this is the most common outcome during a shooting on campus).

Teen turned himself in through a process facilitated by a community violence prevention group around 9pm (8 hours after the shooting).

How did the 17-year-old student escape so quickly after shooting five classmates inside Wilmer-Hutchins High in Dallas?

The student ran from campus before police arrived and flagged down a passing driver. The teen said he was in a car wreck and needed a ride to his father. The driver dropped him off at a nearby gas station (interview below).

When the driver saw the news about the school shooting later in the afternoon, he realized the kid he picked up was probably the assailant, so he called police. The man also realized the teen had a shirt balled up in his lap that probably had his gun hidden inside.

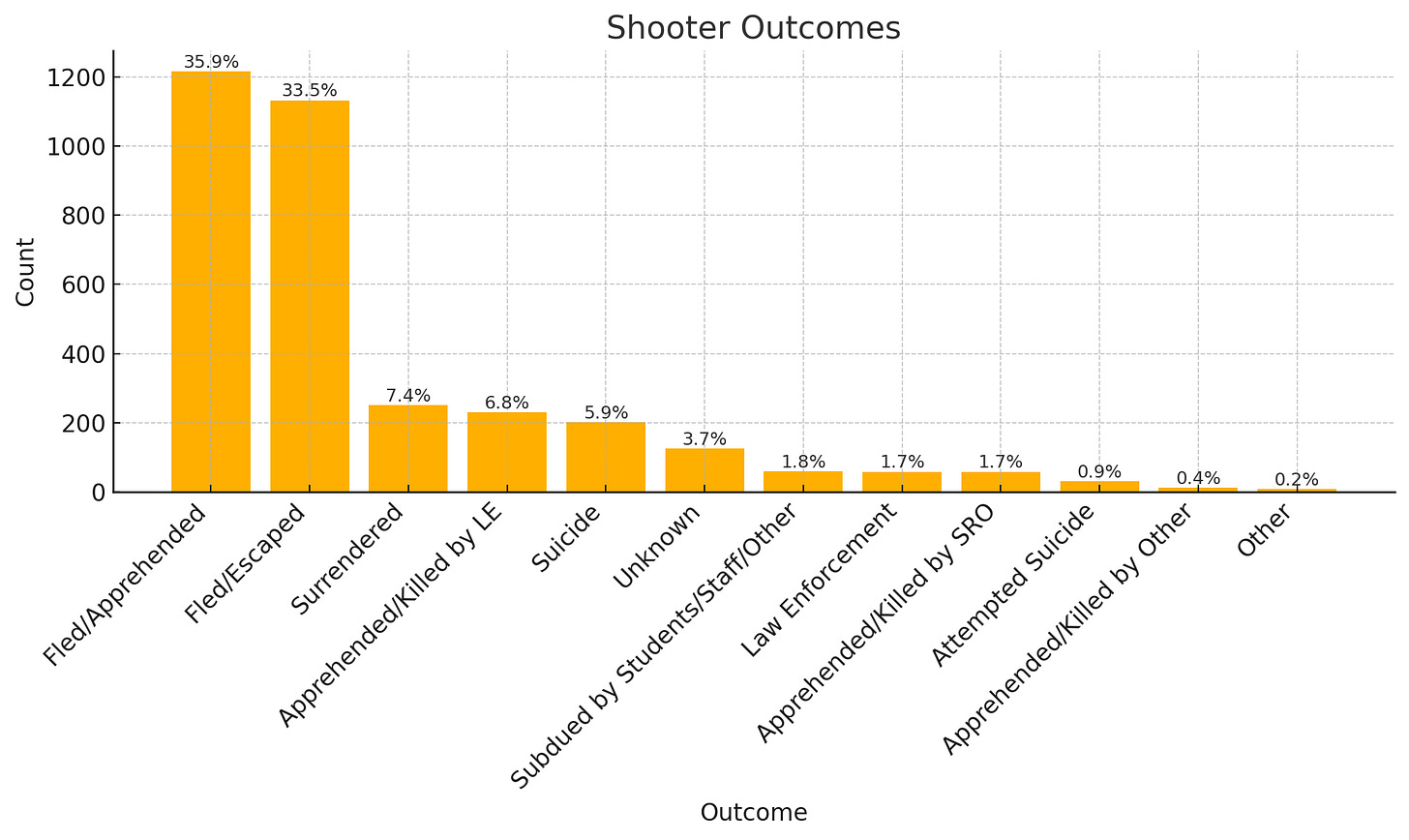

This situation in Dallas is not a surprise because 76% of shootings on campus end with the shooter fleeing before police get to the school. Only 8% of shootings end with police arresting or shooting the assailant on the campus. If I was a police chief, instead of sending every available officer directly to the school to search inside the building, I would have some officers search a one-mile perimeter around the campus for a fleeing suspect.

Data on incident outcomes

From looking at more than 3,000 shootings at k-12 schools, it’s very rare for someone to wait around for police to arrive and find them. Going all the way back to the 1960s, police have never found a school shooter hiding inside a closet, yet most active shooter training sessions and every police response involves searching every room of the campus.

69.4% of shootings end with the assailant fleeing from campus before police arrive.

It’s 10x more likely for the shooter to flee than for them to be apprehended or killed on campus by police officers. If there is a School Resource Officer (SRO) already on campus, that officer captures the perpetrator 1.7% of the time.

Looking at just ‘active shooter’ incidents where the perpetrator attempts to shoot at as many random people as possible, the percentage of incidents ended by police increases to 19% (21% including the SROs).

In 79% of these ‘active shooter’ situations, the attack is over, or the attacker has fled, before police arrived.

In the active shooter cases, the outcome doesn’t correlate with the number of victims. There are high fatality shootings like Parkland where the shooter fled from the campus, high fatality shootings like Columbine where the shooters commit suicide, and high fatality shootings like Uvalde where the shooter was killed by police. There are also low fatality active shooter incidents across each outcome.

This means that in 4/5 of worst case “active shooter” scenarios, having tactical officers with rifles and shields search every room of the school has no purpose other than giving cable news crews something exciting to film.

Here is how some recent planned attacks at schools ended:

2025: Antioch High School (TN) shooter killed himself before police arrived. He had additional ammo when he killed himself.

2024: Abundant Christian Life School (WI) shooter killed herself before police arrived. She had a second loaded gun insider her backpack that wasn’t fired.

2024: Feather River Adventist School (CA) shooter killed himself before police arrived.

2024: Apalachee High (GA) shooter stopped firing and surrendered to campus police officers.

2024: Perry High (IA) shooter killed himself before police arrived.

2023: UNLV (NV) shooter walked outside with other students and faculty who were being evacuated by police.

2022: CVPA High (MO) shooter waited in the hallway for 2 minutes and 30 seconds for police to find him. He had more than 300 rounds of unused ammo.

2022: Uvalde (TX) shooter sat inside a closet while students were still alive inside the same classroom and he still had extra ammo.

2022: Edmund Burke School (DC) sniper edited Wikipedia pages until police got to his apartment despite having multiple rifles and 700 rounds of unused ammo. He killed himself before police entered.

2021: Oxford High (MI) school shooter put his gun down and surrendered.

2019: Saugus High (CA) school shooter killed himself with his last bullet 16 seconds after the shooting started.

2019: Students inside a locked classroom with the student assailant subdued the STEM High (CO) school shooter.

2018: Santa Fe High (TX) school shooter barricaded inside a classroom for 30 minutes before surrendering to police.

2018: Parkland (FL) shooter put down his rifle and walked away with a crowd of students leaving the campus.

2018: Marshall County High (KY) shooter put his gun down and surrendered.

Looking at the trends over time, the distribution of different outcomes remains roughly the same across each decade. Even as school security, lockdown training, and response planning/training has increased, the same percentage of shooters still flee before police arrive.

Looking at the outcomes by school level, it’s interesting that elementary, middle, and high schools all have roughly the same distribution of shooters fleeing.

What does this all mean?

There is a myth perpetuated by police training that shootings don’t end until police stop them. From the Department of Homeland Security Active Shooter Response Handbook: Typically, the immediate deployment of law enforcement is required to stop the shooting and mitigate harm to victims.

Basing training and procedures on assumptions rather than facts has harmful consequences:

Sending hundreds of police officers into a school is expensive and dangerous (each officer had a loaded gun that can accidentally be fired).

Students suffer acute psychological trauma while they are locked down inside classrooms as police search the school.

EMS care for injured victims is delayed until police give the “all clear” or a specially trained “tactical EMS teams” arrive.

To have the best chance of catching a school shooter immediately, police should be searching a 1-mile area around a school campus for someone who is fleeing.

We need to analyze data to understand the real-world circumstances and outcomes of these attacks rather than just writing plans and procedures based on assumptions.

Read more: Does the killing really continue until police engage a school shooter?

David Riedman is the creator of the K-12 School Shooting Database, Chief Data Officer at a global risk management firm, and a tenure-track professor. Listen to my weekly podcast—Back to School Shootings—or my recent interviews on Freakonomics Radio, New England Journal of Medicine, and my article on CNN about AI and school security.