'Love Island' can help prevent school shootings

This viral reality TV show is a case study in social exclusion, in-group/out-group conflicts, emotional regulation, and the power of personal narratives.

Love Island is a reality dating show where a group of singles ("islanders") live together in a luxurious villa under constant surveillance. The format revolves around “coupling up” to avoid elimination, with regular "recouplings" that rematches pairs of contestants, public votes from viewers on couples, surprise twists, and bombshell arrivals of new islanders that keep tensions high. Contestants compete not only for love, but also for fame and a $100,000 cash prize.

At the finale, one partner is given an envelope with the full prize and must choose to either split the money with their partner or keep it all in a final test of trust and love.

While the show started in the UK back in 2005, this summer the reboot went viral thanks to viral TikTok clips, meme-worthy moments, live watch parties selling out bars (like the news story above from Sacramento) and daily episodes that stream simultaneously in the U.S. and U.K. With real-time fan voting through mobile apps, strategic partnerships with streaming platforms, and influencer crossovers, Love Island transformed into a pop culture phenomenon that’s defining the summer of 2025.

But there is more to this story than just another trashy reality TV show. Underneath the glittery drama is a case study of human behavior. The show is essentially a social experiment that’s packed with lessons about belonging, emotional regulation, peer intervention, and the desire to be seen. Surprisingly, these themes echo many of the same factors that can either contribute to the crisis of a teen spiraling towards violence or show how peer connections can prevent situations from escalating.

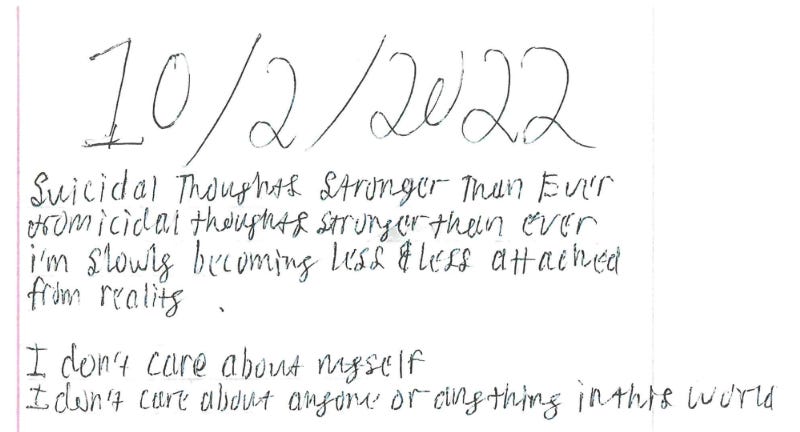

I’ve recorded two podcasts with a forensic psychologist going page-by-page to explain the manifestos of school shooters and their writings express the same themes as the show:

Ep 43. Forensic psychologist explains the Nashville school shooter's journals

Warning: School shooter's manifesto shows failures across American society

Social Exclusion and Peer Intervention

Love Island makes it painfully obvious how much social exclusion hurts. When someone is left out of a coupling or iced out of group dynamics, they spiral into an emotional breakdown. That feeling of not belonging isn’t just reality TV drama, it’s a warning sign. Many school shooters share a history of chronic social rejection, bullying, or alienation.

The social pressure of these situations also compounds the drama because it doesn’t stay private in the villa. If two contestants start spiraling, others can either step in, or make it worse. Sometimes it’s messy, but it’s a form of real-time peer intervention. In schools, peers are often the first to notice when something’s wrong. Teaching students to recognize concerning behavior and speak up (without fear of punishment for either student) is essential.

Another student’s voice can be the most effective early warning system we have because an act of kindness between classmates can prevent someone from committing an attack. In his viral TEDx Talk, Aaron Stark describes how one kid offering him a meal and clean t-shirt kept him from shooting up his school.

If we take anything from this, it’s that social connections can protect people in crisis. Schools that promote peer inclusion, mentoring, and support systems aren’t just being kind, they’re reducing risk.

In-Group/Out-Group Conflict (social identity theory)

Social identity theory explains how people develop their sense of self from the groups they belong to. When self-identity becomes defined by group membership, people strongly favor their in-group. This then creates conflicts and power relationships by rejecting outsiders and attacking other groups (studies of terrorism are rooted in understanding these in-group/out-group dynamics).

On Love Island, this plays out through cliques, alliances, and shifting group dynamics where being "coupled up" or included in the dominant social circle gives contestants status and security. Those who are left out or perceived as different start to struggle emotionally or become targets for exclusion. This shows in real time how quickly in-group/out-group dynamics form and how powerful group identity can be in shaping behavior and belonging.

On Love Island, it’s never just about one person. Every decision in the villa from who gets dumped to who’s forgiven is shaped by the groups. The same is true in schools because teenage school shooters don’t operate in a vacuum, they are part of a school community and group dynamics that include or exclude them.

The decisions of a teen in crisis are shaped by interactions with peers and adults who either respond to or ignore their overt warning signs. Preventing a kid from spiraling to the point of committing a violent public suicide requires understanding and improving the whole social ecosystem around them.

Emotional Regulation

Love Island shows what happens when emotional regulation fails. Someone feels rejected or betrayed, and suddenly there’s yelling, crying, and impulsive decisions. On each episode of the show, adults melt down on national television.

Poor emotional regulation is a key factor in many school shootings, where a perceived injustice turns into a catastrophic reaction. That’s why emotional literacy, conflict resolution, and stress management should be as important in school as math or reading.

Personal Narratives

Love Island thrives on personal narratives as contestants often frame themselves as the hero, the underdog, or the wronged lover.

On Love Island, the personal narrative stories that each islander creates guide their behavior and justify their actions. Similarly, many school shooters build grievance narratives through twisted stories where they see themselves as victims and violence as justice. Interrupting and reshaping these narratives through counseling, building social connections, or restorative practices is the only way to address the root causes of their personal crisis.

Beneath the theatrics, Love Island reveals a powerful truth: people want to be seen. Some contestants stir drama just to stay in the spotlight. That hunger for recognition is deeply human and school shooters who leave manifestos are driven by that same desire for people to notice and remember them. The really tragic part is a school shooter just wants to be acknowledged by any means and when nobody sees them plotting violence, they decide that total destruction is their only option.

That’s why we must build healthy pathways for social visibility and peer validation long before anyone seeks it through a violent public suicide.

A Trashy Island Can Make School Safer

In the end, Love Island is more than a guilty pleasure—it’s a mirror. The show reflects how deeply we crave connection, how fragile identity becomes under pressure, and how quickly exclusion, rejection, or humiliation can escalate into crisis. What happens in the villa may be dramatized for TV, but the group dynamics, emotional volatility, peer loyalty, and personal narratives are the same ones shaping real teenagers in real schools.

The difference is that in Love Island, the breakdowns lead to dramatic exits and tabloid gossip. In American schools, an emotional crisis that continues to escalate without intervention can lead to a tragedy.

If we want to prevent school shootings, we need to stop pretending they are random and unpredictable. The warning signs are not hidden because kids in crisis want to be seen and want to be helped. A kid plotting a school shooting is struggling in plain sight just like the contestants we binge-watch for entertainment.

The drama Love Island packages each hour is the same stuff that forensic psychologists find in mass shooters’ manifestos. Kids in crisis feel invisible, wronged, or hopeless. Luckily the tragic outcomes are preventable. Peer connection, emotional education, and deescalating conflicts are life-saving interventions. If a reality dating show can teach us anything about preventing the next school shooting, it’s that being seen and accepted might be the most powerful protective factor we have.

David Riedman is the creator of the K-12 School Shooting Database, Chief Data Officer at a global risk management firm, and a tenure-track professor. Listen to my weekly podcast—Back to School Shootings—or my recent interviews on Freakonomics Radio, New England Journal of Medicine, and my article on CNN about AI and school security.