Is school security a one-way or two-way door?

Amazon executives need to classify every decision as either a "one-way door" (no going back) or "two-way door" (easily reversible) to help judge the risks and impacts of their choices.

During the early days of Amazon when the company was still just an online bookstore, Jeff Bezos would discuss every new idea with the entire management team. Every proposal received the same intense scrutiny, as if it had irreversible, company-altering consequences. Bezos eventually realized this approach is hindering innovation because many decisions were easily reversible and shouldn’t involve time and input from everyone.

The solution Bezos discovered was to distinguish between “one-way door” decisions (those that are nearly impossible to reverse) and “two-way door” decisions (those you can quickly revisit and fix if they go awry).

Bezos wanted to empower Amazon leaders and employees to move faster when the stakes were lower, while saving the more rigorous, high-stakes deliberation for only truly irreversible choices. By asking a simple question—“Is this a one-way door or a two-way door?”—teams could avoid gridlock. What began as a practical solution to decision paralysis in a rapidly changing start-up became a foundational principle that guides Amazon’s culture and management processes to this day.

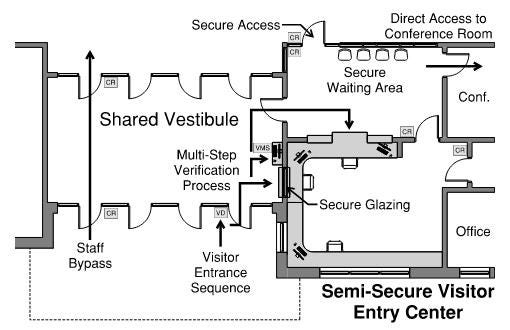

School officials are constantly considering new security procedures, staff, and equipment. If they’re debating whether to try a new visitor management system (something that could be easily swapped out if it doesn’t work) or renovating the entire buildings with ballistic doors and windows (a choice that can’t be undone once construction starts) this is the time to use Amazon’s “one-way door” versus “two-way door” framework.

One-way door decisions (like structural changes to a building) demand deeper deliberation because they’re effectively permanent, expensive, require ongoing funding to maintain, and controversial to reverse. Two-way door decisions (like a visitor policy) can be quickly tested, adapted, or even tossed if they flop. By borrowing this model from Amazon, school officials can strike a balance between acting quickly to address concerns and taking the time to get irreversible decisions absolutely right.

Look back if you missed it: What is School Security? (School security has four different components: the physical campus, security equipment added to it, procedures and training for how to use the equipment, and personnel to carry out the procedures)

One- vs. Two-way door decisions for schools

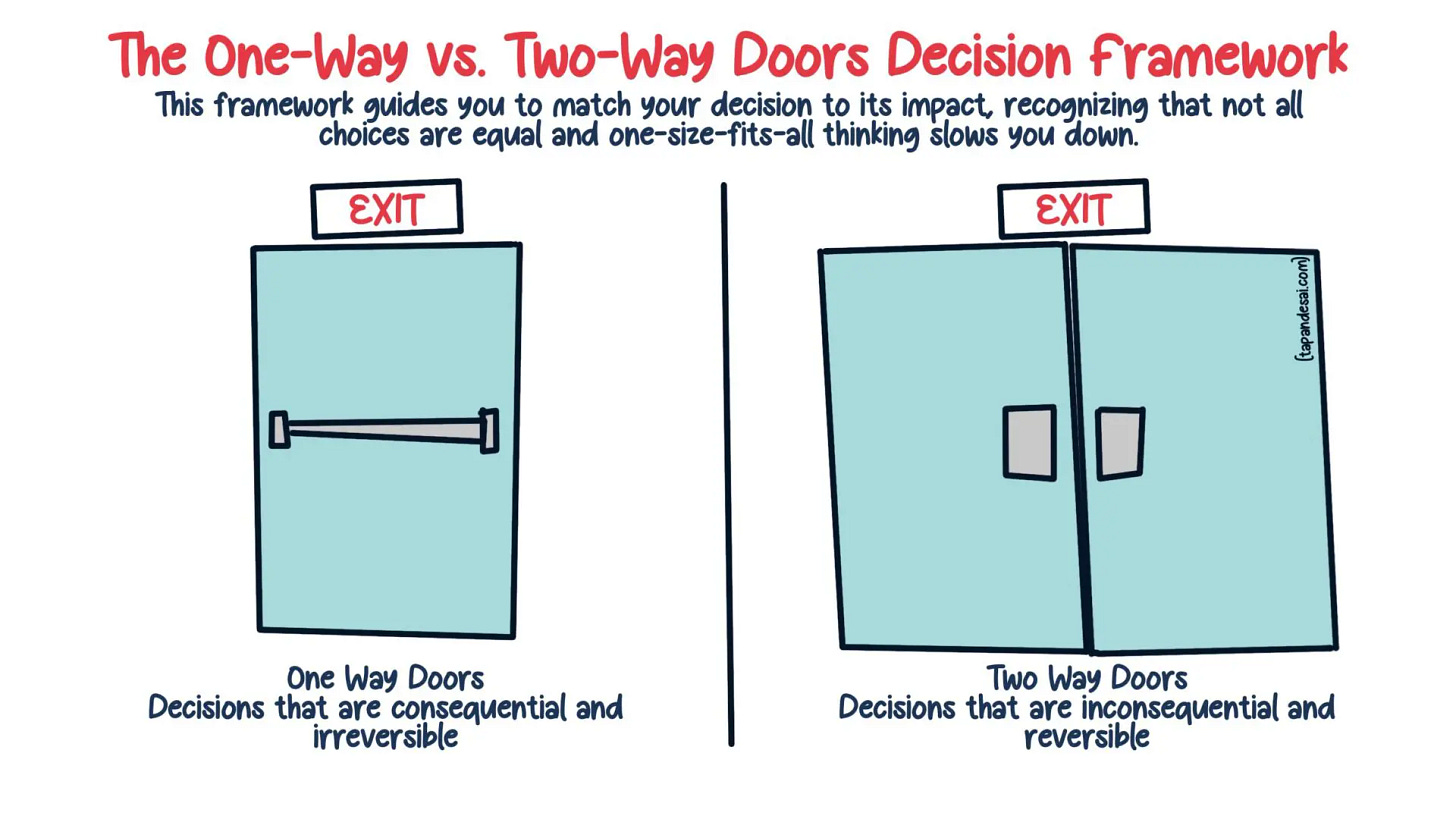

“One-way door” (Type 1) decisions are those that are high-stakes, largely irreversible, and demand a thorough decision-making process. “Two-way door” (Type 2) decisions are lower-risk, more easily reversible, and can often be made quickly with the option to pivot if they don’t work out.

Physical Security at Schools

One-Way Door (“Closed Door”) Decisions

One clear example of a one-way door decision is making permanent structural changes. Installing bullet-resistant glass or constructing secure vestibules at every entrance not only involves a significant upfront cost but also requires navigating building permits, construction logistics, and long-term maintenance. Once these structures are in place, reversing course is both expensive and disruptive, making them difficult to modify or remove if circumstances change. These alterations can also change the culture of the school, signaling a permanent shift in how safety is perceived by students, staff, and the surrounding community.

Another one-way door decision is hiring school resource officers (SROs) or security guards. Contractual agreements and the need for proper training, vetting, and oversight create long-term implications for the district’s budget and operations. Reversing the hiring of staff can be politically sensitive and can significantly damage staff morale, student perception, and community trust if officers are hired and then fired. District-level mandates—like requiring every middle or high school to use metal detectors or conduct daily bag checks—are equally irreversible in practice. Once the district invests in equipment, staff training, and procedures to support daily checks, halting the process questions the rationale of leadership for investment in the first place.

Two-Way Door (“Open Door”) Decisions

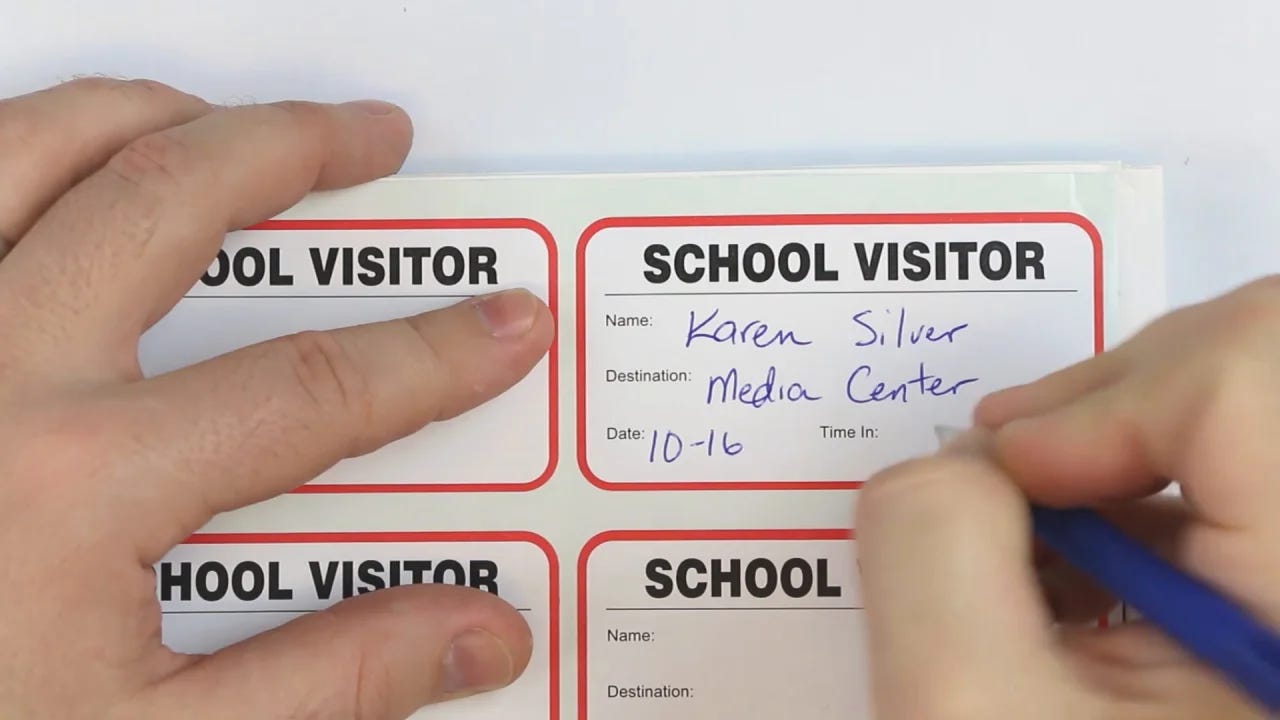

In contrast, two-way door decisions give school administrators more flexibility and freedom to experiment. One example is pilot testing new access-control, such as a trial visitor check-in system or temporary ID badges. If after a few months the system proves cumbersome or ineffective, it can be phased out with relatively little sunk cost or disruption to learning.

Another example is introducing voluntary security drills or testing a new style of lockdown or evacuation procedure. These drills can be paused, scrapped, or overhauled based on input from participants and lessons learned from recent incidents. Entering into short-term security contracts—such as bringing in private security for a semester—allows schools to evaluate whether the added presence actually meets their goals. If the feedback is negative or the results are underwhelming, administrators can simply choose not to renew the contract.

Threat Assessment Teams and Reporting Systems

One-Way Door (“Closed Door”) Decisions

An example of a one-way door decision in threat assessment is labeling a student as “high-risk” and placing them in an alternative education setting. Such a designation often follows a student’s record and impacts their academic pathway, social interactions, and overall school experience. Reversing this decision typically requires an extensive appeal process, as administrators must carefully reevaluate the student’s behavior and potential risk to others. Even if a student is eventually moved back into mainstream classes, they have still missed time at school plus the stigma of having been labeled “high-risk” and transferred can affecting peer and teacher relationships.

Another one-way door decision is a mandatory expulsion for a student deemed dangerous. Once the student is removed from school, the process of reintegration or record revision becomes legally and administratively complex. Expelled students face challenges in reestablishing trust and friend/support networks within the new school community (if a new school will accept them). They may also deal with negative long-term academic, employment, and psychological consequences because being expelled is a scarlet letter that can follow them for years.

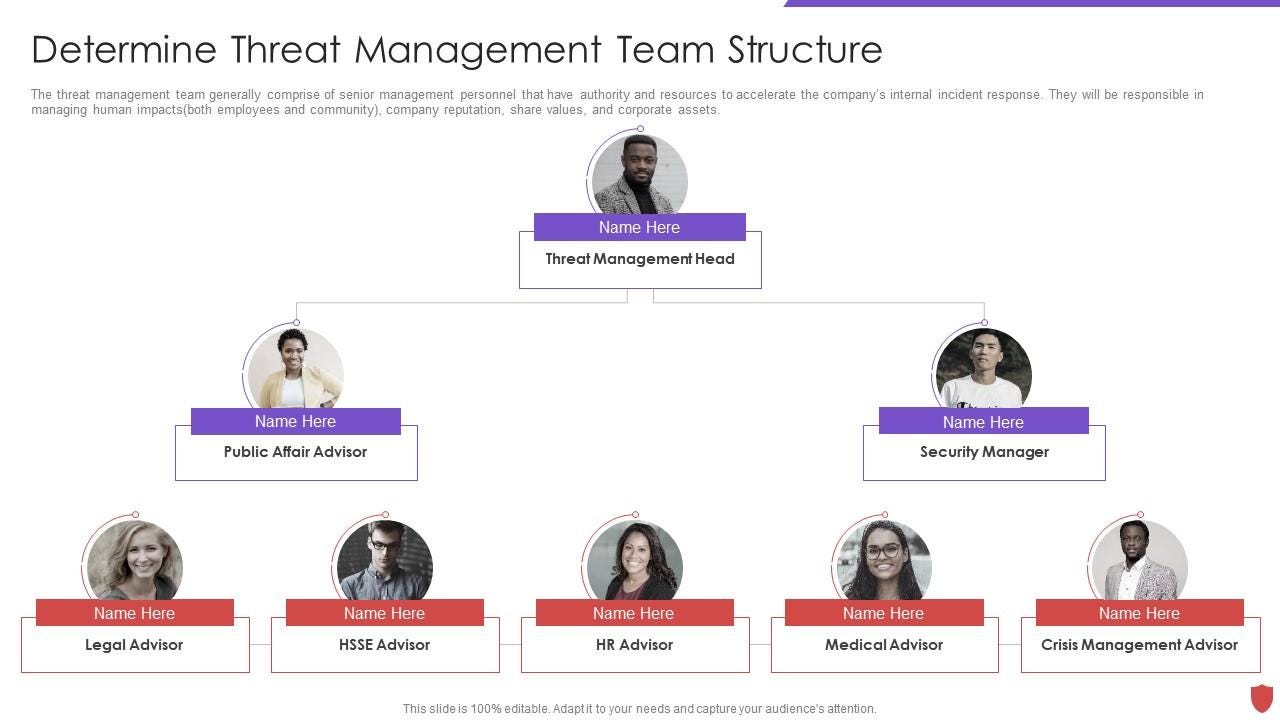

Creating a comprehensive threat assessment team infrastructure can also be a one-way door choice when it involves long-term commitments and large budgets. Hiring a team of professionals—ranging from psychologists to security experts—may require the district to commit to hiring senior-level staff, signing multiple-year contracts, and sending staff to specialized training. Likewise, purchasing enterprise-level reporting systems and integrating real-time monitoring can be costly and complex to roll back, especially once stakeholders have come to rely on these tools.

The presence of a robust system can raise the expectation that every threat will be identified. If a serious warning is missed despite having invested in these measures, the reputational damage and legal implications can be significant.

Two-Way Door (“Open Door”) Decisions

On the more flexible side of threat assessment, schools might begin with initial interviews and counseling. A threat assessment team can conduct a series of one-on-one discussions with the student, and observe their behavior over time without committing to a permanent label, transfer, or expulsion. If subsequent evaluations reveal that the student’s risk level is lower than initially believed, any measures—such as additional check-ins or small-group counseling sessions—can be scaled back with relative ease. This approach allows schools to address concerns proactively while still preserving the option to adjust quickly as the student’s situation evolves.

Short-term suspensions or supervised monitoring provide another example of a two-way door decision. Instead of immediately expelling a student, administrators might opt for a brief out-of-school or in-school suspension, combined with increased adult oversight or targeted interventions. These measures can be lifted early or restructured if the circumstances change. Similarly, behavior contracts—where the student and parents agree to specific conditions, such as attending counseling sessions—can be adapted or canceled as progress is made. Because these interventions don’t carry the permanence of an expulsion or mandatory transfer, they allow schools to course-correct with far fewer long-term repercussions to the student.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to School Shooting Data Analysis and Reports to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.