Is a bad security strategy worse than no strategy?

Risk management is not moving toward zero overall risk. It's deciding which risks to reduce at the expense of increasing others like balancing on a seesaw.

In my recent podcast episode The Fortress Problem, we discussed three conflicting paradoxes in school security:

Walls that protect against invasion create an entirely new risk from being trapped inside by a siege.

Defenses against an outside attacker are advantages to an insider threat.

Fire safety (lots of exits, open pathways, no barriers, rapid evacuation) is the opposite of physical security (few doors, narrow passages, access control, lockdown).

When both sides of the spectrum have real threats, any action taken to decrease risk in one direction is increasing risk on the other side. We need to realize that risk management is not moving toward zero, it is deciding which threat to address at the expense of another. If the seesaw is balanced right in the middle, neither side is effective (or having fun on a playground).

In the paper by Jack Anderson (my grad school classmate at the Naval Postgraduate School), The Fortress Problem exists because an adversary always has the advantage against a castle. Physical defenses are defined attributes which allow an innovative attacker to do just enough to defeat them. There is an old adage, build a 10-foot wall and they will bring a 12-foot ladder.

When they rely on robustness or complication, positions of strength are only tolerant of stress up to a defined point or of a certain character. For a fortification that fails to adapt, centralization—even of strength—presents a surprising liability. Fortresses concentrate risk.

A grand design for security will not produce grand security. Security requires fewer scripted plans and more improvisation, more diversity, less uniformity, less training with partners, and more learning to work with strangers.

Beyond fortress building and outdated military theory, there are three flawed strategies that are being misapplied to prevent school shootings:

Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design

Broken Windows Policing

Unwinnable Wars Against Ideas

Crime prevention through environmental design

School security consultants, architects, and vendors have sold many school officials on creating campuses that use concepts of “Crime Prevention by Environmental Design”. This sounds good on paper until you actually read the academic articles about it.

From a recent article by The Assembly, How To Design Safer Schools: In an era of mass shootings, architects are striving to create safe spaces for students without making schools into fortresses:

“All security risks cannot be eliminated, but we can do thoughtful planning and design to mitigate unwanted guests and make it more challenging for an intruder,” said landscape architect Renee Pfeifer of Cary-based CLH Design.

These are all good examples of what’s called “crime prevention through environmental design,” said Michael Dorn of Safe Havens International.

The architects think about security in unconventional ways. In some places, they want to create visibility; in other places, they want barriers.

Visible changes to the environmental design of a store, shopping mall, or residential property can impact the rate of property crime. There is no empirical evidence showing that changes in physical design features decrease violent crime (see: seven misconceptions of situational crime prevention by the original author of the theory).

The concept of building design reducing property crime came from a study of residential burglaries in the 1970s (Clark, Situational Crime Prevention). Lowering the height of shrubs, designing sight lines from the street to doors and windows, installing fences, and adding lighting all make a home less attractive to a residential burglar.

Unlike property crimes that are based on opportunity, violent crime is usually committed by someone with a pre-existing relationship with the victim. School shooters are not random opportunists looking for “soft targets”, they are usually current students with a specific grievance directed at the campus. The height of the bushes may deter a thief from breaking into a house, but it doesn’t change the motivation of a jilted ex-lover to murder a former spouse.

It’s also important to note that environmental changes to one property don’t lower the overall rate of burglary in a neighborhood, they just displace property crime by making the house next door a better target. This is a distinctly different concept from the hypothesis (unproven) that fortifications deter school shooters and mass shooters. School shootings and mass shootings are usually highly personal and deliberate attacks by an insider (e.g., student, employee, frequent patron) with a known grievance. Unlike a burglar looking for the easiest house to target, their specific school is the only target for a teenage assailant.

If a school campus has a problem with burglars, trimming the bushes and adding fences might help. If the goal is preventing shootings, there is no evidence these designs deter a violent offender. In fact, spending limited funding on physical designs instead of social workers and crisis intervention programs might be increasing the overall risk of a shooting.

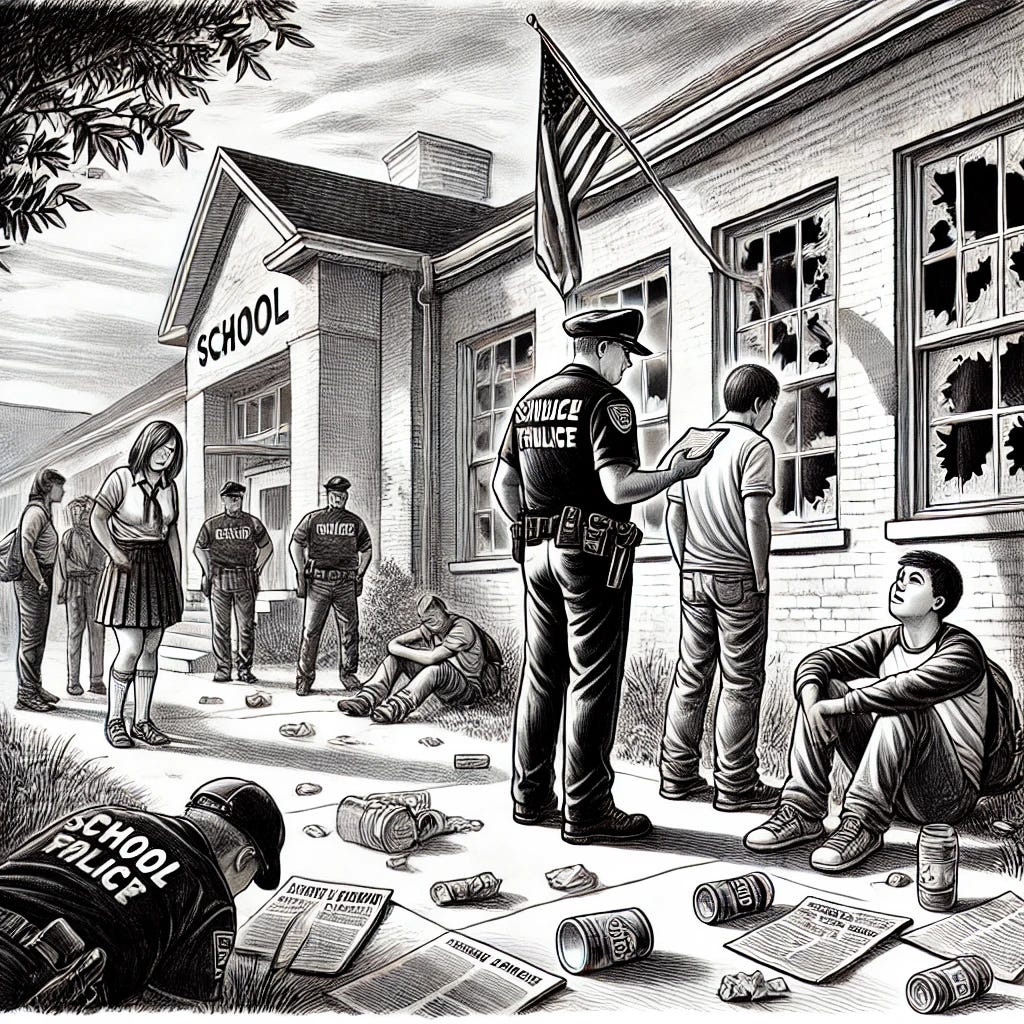

Broken Windows Policing

Broken Windows Theory originated from a 1982 article titled "Broken Windows" by social scientists James Q. Wilson and George Kelling, published in The Atlantic Monthly. The authors argued that visible signs of disorder and neglect—such as broken windows, graffiti, and public loitering—can lead to an environment that encourages more serious crime.

40 years later (after progressive date-driven police departments have abandoned this strategy) schools are adopting broken windows policing concepts through focus on visible presence as a deterrence (ineffective based on studies) and zero tolerance discipline for minor offenses (also shown to be ineffective). Applying these two ineffective strategies have become legislative mandates in Florida and Texas.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to School Shooting Data Analysis and Reports to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.