Danger of dismantling public education

Federal dollars go to school police and security, assisting disabled students, free lunches for low-income kids, and keeping the lights on in the poorest, rural school districts.

Schools—and school shootings—sit at the center of a complex web of interconnected social and political issues. Federal policy decisions impact every part of a student’s day from a free breakfast in the morning to paying the salary of a school police officer who might (or might not) arrest them for misbehavior depending on the policies decided by elected officials.

This means that every discussion of student safety, school security, and education is inherently political because schools are public institutions governed by elected politicians at the local, state, and federal level.

This week, we will find out if professional wrestling executive Linda McMahon ($3.2 billion net worth) is confirmed as the Secretary of Education. She seems like a strange choice because she lacks experience or qualifications for this position, but that’s exactly the purpose of her appointment. President Trump described her role as being to “put herself out of a job” by dismantling the department. She plans to:

“Fund education freedom, not a government-run system,” McMahon said in her opening statement before the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee.

In reality, the Department of Education has very little power to control curriculums or what teachers do in their individual classrooms. Most federal dollars fund school police officers, support students with disabilities (e.g., care aid for a paralyzed kid in a wheelchair), give free/reduced lunches for low-income kids, and grants to cover operating costs at the poorest (mostly rural) school districts.

Here is my conversation with an education economist about it (Ep 31. From public school teacher to economic advisor at The White House).

Aside from the disabled kids who won’t be able to eat, drink, or use the bathroom all day without the federal funding for the staffer who cares for them at school, dismantling the Department of Education is part of a more dangerous pattern. Over the last century, authoritarian rulers changed the foundational structure of public education as they took control of countries across the world. Authoritarians follow the same pattern:

Rise to power by claiming they will make life better for the poor and working class.

Change public education and rewrite history to teach only their self-serving version of it.

Empower the richest elites to control even more wealth while the people get poorer.

This process works over and over in different countries and time periods because people who don’t have what they need to survive focus their attention on food and water, not freedom. An authoritarian tells a story about how they can get more bread (or cheaper eggs), but it’s a false promise. Once an authoritarian has power, they don’t need to give the people anything.

This is why authoritarians thrive in the weakest societies when the basic needs of the citizens aren’t being met. While only 11% of U.S. citizens live below the poverty line, many voters were tricked into thinking a record high economy is in a recession and voted based on promises to make consumer goods like eggs and gasoline cheaper.

But when a dictator rises to power, the quality of life for the average person only gets worse. Across the 1900s, the world saw authoritarians come to power in small and large countries on every continent including Germany, the Soviet Union, Italy, China, North Korea, Cuba, Cambodia, and Romania.

Political violence at schools

The biggest danger from the close connection between authoritarian power and public education is that it creates an environment where schools become targets for politically motivated violence.

For example, the Beslan School Siege in Russia took place on September 1, 2004. The standoff lasted three days and involved more than 1,100 people (~750 children) held hostage inside the school. The attack ended with the deaths of 334 people including 186 children.

Three weeks after the attack, Chechen terrorists issued a statement claiming responsibility for the attack and described the attackers as a "brigade of martyrs". Back in 2003, Chechen terrorists were angered by Russia’s military crackdown, human rights abuses, and the suppression of Chechnya’s aspirations for autonomy. This fueled a deep-seated resentment that motivated violent retaliation. Chechen terrorists targeted a school in Russia to maximize public shock, attract international attention, and exert pressure on the Russian government by choosing a vulnerable target that would evoke strong emotional and political reactions.

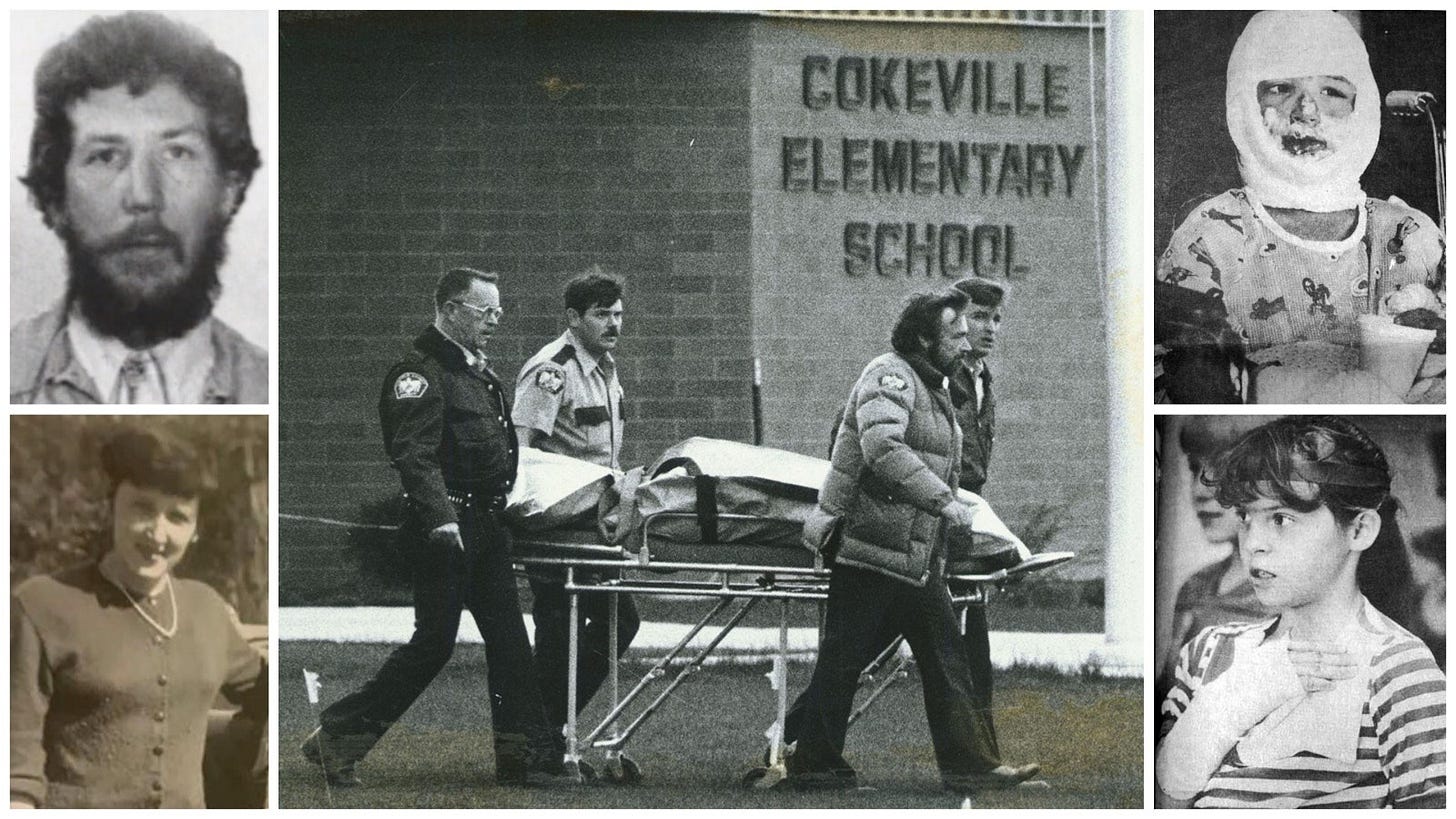

Two decades earlier, the Cokeville Elementary School (WY) hostage crisis occurred on May 16, 1986. David Young and his wife Doris Young took 136 children and 18 adults hostage inside the school. The Youngs had ties to white supremacist groups, including the Posse Comitatus and the Aryan Nations. They demanded two million dollars per hostage and an audience with President Ronald Reagan (political demand).

The couple was armed with ten firearms and an improvised gasoline bomb. They corralled students and faculty into a single room as they waited for their ransom. Two and a half hours into the standoff, Doris Young accidentally detonated her gasoline bomb. She was severely burned that David Young fatally shot her. When he realized the situation wasn’t going to end well, he killed himself.

Political anger has already been directed at public education in the United States and appointing an intentionally inflammatory wrecking ball like Linda McMahon to Secretary of Education further escalates this tension. Given the modern political climate and violent anti-government rhetoric from far-right groups, it’s not hard to imagine domestic terrorist attacking a school. Schools are a symbol of the government institution and have been criticized by far-right groups for decades with claims of indoctrination and “grooming” students.

A school curriculum that focuses narrowly on a white Christian worldview—especially if it marginalizes or demonizes other racial, religious, or cultural identities—can create a volatile environment where extremist ideologies thrive. Students or community members who feel validated by such content may develop a sense of moral or historical justification for animosity against those viewed as “outsiders” or “threats.”

This sense of perceived righteousness can embolden violent behavior. Individuals already leaning toward extremist beliefs might interpret the curriculum’s biased messages as a call to defend their identity and values through aggression. Consequently, schools could become targets for both domestic and foreign terrorism, as attackers—feeling empowered by the exclusivist narrative—may believe they are standing against a system they perceive as diluting or attacking their rights, religion, or heritage.

Before the foundations of the US public education system can be destroyed by billionaires like McMahon and Musk, Trump needed to rise to power by promising prosperity for the poor and working class (the same populations who are completely dependent on public education for their children).

Part 1: Promises of more food and wealth

Authoritarian leaders often justify their concentration of power by promising prosperity—more food, better living conditions, and greater wealth. Of course, the reality of these promises falls short. Under every authoritarian in modern history, the living conditions of all citizens—except the leader’s inner circle of oligarchs—got much worse.

Joseph Stalin (Soviet Union, 1920s–1953)

Promise: Stalin promised to transform the Soviet Union from a largely agrarian society into an industrial superpower. Through the Five-Year Plans, he claimed the country would experience rapid economic growth and increased agricultural output to feed everyone.

Reality: While industrial output did grow, Stalin’s collectivization of agriculture caused massive famines (e.g., the Holodomor in Ukraine) and widespread suffering. While millions starved, there was widespread political repression through purges and labor camps.

Adolf Hitler (Nazi Germany, 1933–1945)

Promise: Hitler promised economic recovery, full employment, and an end to the food shortages that had plagued Germany after World War I and during the Great Depression. He promoted “Lebensraum” (“living space”), claiming expansion into Eastern Europe would secure agricultural land to feed the German people.

Reality: Initially, rearmament and public works projects (e.g., Autobahn construction) reduced unemployment. However, this short-term economic boost depended heavily on military spending and plundering occupied territories. The Nazi regime’s war of expansion brought catastrophic devastation and widespread hunger to occupied regions.

Benito Mussolini (Fascist Italy, 1922–1943)

Promise: Mussolini vowed to restore the glory of the Roman Empire and touted grand economic initiatives such as the “Battle for Grain,” aimed at achieving self-sufficiency in food production to make Italians wealthier and more independent.

Reality: Although some measures increased domestic grain production, Italy’s economy remained weak, and the regime’s aggressive foreign policy diverted resources away from the needs of ordinary Italians. Mussolini’s promises of prosperity failed to materialize, and living standards were stifled by military expenditures and corruption.

Mao Zedong (People’s Republic of China, 1949–1976)

Promise: Mao promised to modernize China swiftly and bring about a communist utopia. During the Great Leap Forward (1958–1962), he claimed it would rapidly increase steel and grain production, leading to abundance for all.

Reality: The Great Leap Forward was disastrously mismanaged. Officials inflated production figures, which led to severe shortages and one of the deadliest famines in history (the Great Chinese Famine). While Mao sought to industrialize China quickly, the policies led to tremendous human suffering and millions of deaths.

Kim Il Sung (North Korea, 1948–1994)

Promise: Kim Il Sung assured North Koreans that the Juche (self-reliance) ideology would lead to independence, prosperity, and a strong economy providing abundance for all. His successors, Kim Jong Il and Kim Jong Un, have continued to promise better lives and ample food.

Reality: The North Korean regime’s centralized control, heavy militarization, and international isolation have caused periodic famines (such as the Arduous March in the 1990s) and chronic food shortages. Despite official propaganda depicting an economically successful state, much of the population has experienced hardship and malnutrition.

Fidel Castro (Cuba, 1959–2008)

Promise: Fidel Castro led the Cuban Revolution promising social justice, land reform, and improved living standards. He assured Cubans that the socialist system would raise incomes, provide abundant food, and eliminate inequality.

Reality: While Cuba did achieve gains in literacy, healthcare, and education, centralized economic planning and dependency on Soviet subsidies led to chronic shortages and economic stagnation. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Cuba experienced the “Special Period,” marked by severe rationing of food and basic goods.

Pol Pot (Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, 1975–1979)

Promise: The Khmer Rouge claimed that by abolishing cities, private property, and class distinctions, they would create an agrarian utopia with plentiful food and equality for all Cambodians.

Reality: In practice, forced evacuations to rural labor camps, combined with brutal policies and paranoia-driven purges, resulted in widespread famine, disease, and the deaths of an estimated 1.7 million people—one of the worst genocides of the 20th century.

Nicolae Ceaușescu (Romania, 1965–1989)

Promise: Ceaușescu pursued a brand of nationalist communism, promising modernization and prosperity through grand state projects and centralized planning. He touted self-sufficiency and encouraged large-scale agricultural initiatives.

Reality: His policies led to severe austerity measures in the 1980s as the regime attempted to pay off foreign debts. Basic goods, including food and heating, became scarce. Lavish projects (like his colossal “People’s House”) drained resources, while ordinary Romanians experienced rationing, long queues for basic necessities, and declining living standards.

Authoritarian rulers often come to (or retain) power with sweeping promises to fix economic or social crises, claiming that only a strong hand can overcome obstacles that democratic or pluralistic systems cannot.

Control of media and public discourse allows these regimes to broadcast positive messages about upcoming prosperity while suppressing evidence of failure or dissent. Maintaining control of this messages and preventing people from realizing that their lives are getting worse requires control over education.

Part 2: Transform public education into indoctrination

Authoritarian regimes recognize the strategic importance of education in shaping loyalty and their self-serving worldview. As a result, dictators and strongmen have historically made sweeping changes to curricula, teaching methods, and the overall organization of schools and universities.

Joseph Stalin (Soviet Union, 1920s–1953)

Centralized Control: The Soviet government took full control over educational institutions, deciding curricula, textbooks, and the ideological content taught to students.

Ideological Indoctrination: Marxist-Leninist doctrine became mandatory in all levels of education. Textbooks were revised to praise Stalin’s leadership and the Communist Party, while dissenting perspectives on history or politics were systematically excluded.

Technical Emphasis: Under the Five-Year Plans, the USSR significantly expanded its network of technical schools and universities to produce skilled workers and engineers to drive industrialization.

Rewriting History: Soviet historiography was constantly updated to align with current political goals and to erase or diminish the achievements of Stalin’s rivals.

Adolf Hitler (Nazi Germany, 1933–1945)

Nazification of Curriculum: Under the Ministry of Education, German schools were forced to adopt Nazi ideology in every subject.

Racial Teachings: Biology and anthropology classes incorporated racist theories and glorifying “Aryan” heritage while denigrating other groups, especially Jews.

State Youth Organizations: The Hitler Youth (for boys) and the League of German Girls were effectively an extension of the education system, emphasizing loyalty to Hitler, physical fitness, and militaristic values.

Purge of Academics: Jewish teachers and professors, as well as those critical of the regime, were dismissed. Educational institutions were purged of “unreliable” elements to ensure uniformity in thought.

Benito Mussolini (Fascist Italy, 1922–1943)

Fascist Youth Organizations: Similar to the Nazi model (though developed earlier), Mussolini’s regime ran the Balilla and Avanguardisti (youth groups) to instill fascist values and loyalty to Il Duce.

Propagandistic Curriculum: Textbooks and lessons stressed Mussolini’s achievements and fascist ideology, promoting nationalism and the idea of a resurrected Roman Empire (e.g., Make Italy Great Again).

Centralized Reforms: Mussolini placed schools under state control, ensuring that teachers were party loyalists.

Cult of Personality: Mussolini’s image and quotes were prominently featured in classrooms, fostering an environment of deference to the leader.

Mao Zedong (People’s Republic of China, 1949–1976)

Mass Literacy Campaigns: After 1949, the Communist Party launched campaigns to improve literacy, seeing education as vital to building a socialist society.

Ideological Purity: Mao’s writings, especially the “Little Red Book,” became core texts. During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), formal education was heavily disrupted as students were encouraged to denounce “counterrevolutionary” teachers.

Red Guards and School Closures: Many schools and universities were closed or paralyzed during the Cultural Revolution, with students turning into political activists (the Red Guards) instead of attending traditional classes.

Down to the Countryside Movement: Urban youths were sent to rural areas to “learn from the peasants,” drastically curtailing formal education for a generation.

Kim Il Sung (North Korea, 1948–1994)

Juche Ideology: Education is founded on Juche (self-reliance) principles, with loyalty to the Kim family as the cornerstone. The curriculum heavily emphasizes the biographies and “accomplishments” of the supreme leaders.

Total State Control: Private or independent educational initiatives are non-existent. The government directly manages all schools, from primary to university levels.

Limited Access: While primary education is officially universal, resources are scarce, and only the elite and politically reliable families gain access to high-quality secondary and tertiary education (much like the impacts of defunding/destroying the U.S. Department of Education).

Propaganda over Scholarship: Texts focus largely on North Korean revolutionary history, demonizing enemies (notably the U.S. and South Korea). Subjects like science and technology also must incorporate ideological lessons.

Fidel Castro (Cuba, 1959–2008)

Nationalization of Education: After the revolution, all private and religious schools were nationalized.

Literacy Campaign: A massive campaign in the early 1960s dramatically improved basic literacy across the island, heralded as one of Castro’s major achievements.

Socialist Curriculum: Schools and universities incorporated Marxist-Leninist principles, emphasizing socialist ethics, history of the revolution, and the role of the Communist Party.

Centralized Management: The government set curricula nationwide, focusing on ideological conformity and loyalty to the revolution.

Pol Pot (Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, 1975–1979)

Anti-Intellectualism: The Khmer Rouge viewed intellectuals and educated individuals as enemies of the new agrarian order (much like higher education, science, and medicine are the first targets being defunded by the Trump Administration). Schools were shut down, books destroyed, and teachers were targets for persecution.

De-Urbanization: Students and teachers were forced into the countryside to work in collective farms. Formal education effectively ceased to function during this period.

Eradication of Traditional Education: The Khmer Rouge aimed to reset the country to “Year Zero,” eliminating any formal or traditional learning as “bourgeois” or foreign-influenced.

Nicolae Ceaușescu (Romania, 1965–1989)

Centralized, Ideological Curriculum: The Communist Party under Ceaușescu exercised tight control over schools, infusing them with nationalist and socialist ideology.

Personality Cult: Textbooks glorified Ceaușescu and his wife, Elena, portraying them as visionary leaders. Teachers were pressured to conform to state narratives and praise the regime’s accomplishments.

Expansion with Limits: While Romania did expand educational access, quality suffered as resources were redirected toward grandiose projects and debt repayment.

Restriction on International Collaboration: Academic institutions had limited contact with Western scholars or institutions, stifling research and access to current scientific developments.

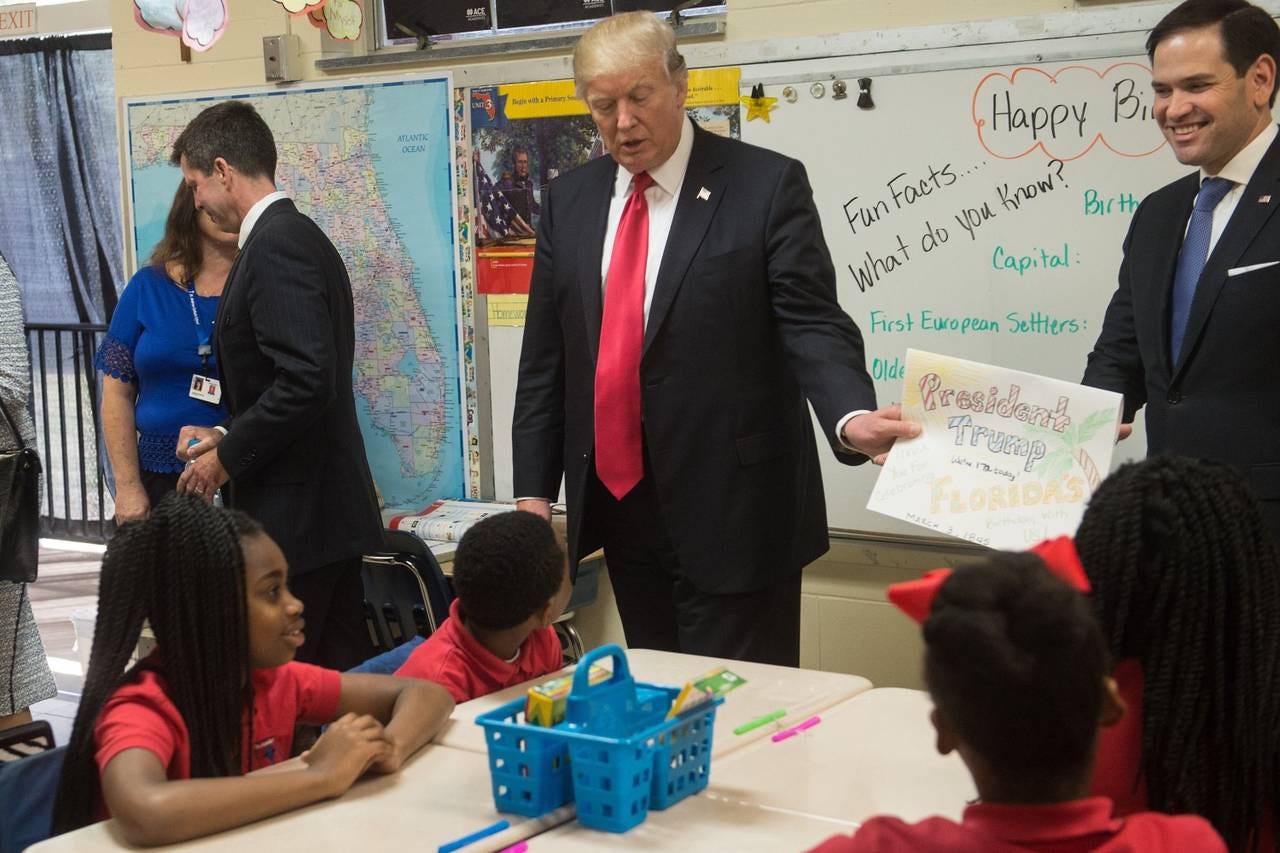

President Trump’s education proposals—particularly around “patriotic education,” school choice, and combating perceived liberal bias—show his desire to reshape national identity and ideology through schools. While other authoritarian regimes can rewrite textbooks, criminalize dissent, and uniformly enforce ideological education, even President Trump still faces institutional checks (for now) that limit sweeping reforms and preserve educational autonomy at the state and local level.

If President Trump’s vision for “patriotic education” goes unchecked, it could undermine the critical thinking skills essential to a democracy. A federally endorsed curriculum that dismisses complex or unflattering (for white Christians) parts of US history risks turning classrooms into echo chambers of state-approved narratives. Over time, this will erode students’ ability to analyze issues independently while fueling division and limiting exposure to different viewpoints.

Drawing parallels to authoritarian regimes that employ education as a tool for rigid ideological indoctrination, this push for a singular “patriotic” curriculum threatens the foundational principles of the United States’ public education system.

Part 3: Concentrate wealth and power into a circle of elites

Why is a billionaire like Linda McMahon who has no experience in public education nominated for the Secretary of Education?

Authoritarian regimes reshape their countries’ social hierarchies by co-opting the richest elites for political and economic gain. A small group of the ultra-wealthy who are tied directly to the dictator (or pay their way in) emerge with privileged access to resources, political influence, and power.

Joseph Stalin (Soviet Union, 1920s–1953)

Under Stalin, the Bolsheviks systematically dismantled the traditional elite that had existed under the Russian Empire. Landowners, industrialists, and wealthy peasants (kulaks) were dispossessed or targeted for persecution, notably during collectivization. In their place rose the nomenklatura—a class of high-ranking Communist Party officials who enjoyed privileges like better housing, access to specialized stores, and superior healthcare. While these officials had more status and resources than ordinary citizens, they remained vulnerable to Stalin’s purges if they were perceived as disloyal.

Adolf Hitler (Nazi Germany, 1933–1945)

Germany’s traditional industrialists and financial elites initially viewed Hitler with skepticism, but many soon aligned with the Nazis once it became clear that the regime would restore economic stability—and, for some, deliver lucrative military contracts (just like Elon Musk’s $16,000,000,000 in federal defense contracts).

Prominent business magnates like Gustav Krupp and companies such as IG Farben and Siemens profited immensely from Nazi rearmament. In exchange, they supported Hitler’s politics—either tacitly or directly—and benefited from the suppression of labor unions. While some wealthy individuals lost status or were persecuted (especially if they were Jewish), industrial and financial elites that cooperated saw their fortunes grow.

Benito Mussolini (Fascist Italy, 1922–1943)

Mussolini sought a corporatist state where government, business, and labor were meant to cooperate under fascist oversight. Established industrialists and large landowners typically retained their wealth, provided they supported Mussolini’s regime. Fascist policies—such as the “Battle for Grain”—saw landowners benefit from subsidies and protectionist measures (much like Trump’s plans for tariffs). However, true independent power outside Mussolini’s circle was disfavored because industrialists and economic elites had to show loyalty to the Fascist Party.

Mao Zedong (People’s Republic of China, 1949–1976)

The Communist victory in 1949 led to the sweeping confiscation of wealth from traditional landowners, businessmen, and the Nationalist-era elites. Mao’s government initially co-opted a few wealthy “patriotic capitalists,” allowing them to keep some assets while aiding state projects. However, as Maoist policies radicalized—particularly during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution—any remnants of private wealth were targeted. A new class of powerful individuals emerged who were high-ranking Communist Party officials who commanded resources and influence through party channels.

Kim Il Sung (North Korea, 1948–1994)

From the outset, North Korea’s Juche ideology stressed self-reliance and nationalization of all major industries. Traditional landlords and business owners were dispossessed or fled to the South. Over time, an elite class formed around the Kim family and top Workers’ Party officials, enjoying special privileges such as access to better housing, food, and imported goods. Today, a “moneyed” class known as the donju has emerged in North Korea, thanks to semi-market activities tolerated by the regime. Still, genuine wealth in North Korea hinges on proximity to power and if politics shift, fortunes can be seized and powerful individuals quickly lose their status.

Fidel Castro (Cuba, 1959–2008)

When Castro came to power in 1959, large estates and businesses—most of which belonged to wealthy Cuban families or U.S. corporations—were nationalized. Many of Cuba’s pre-revolution elites fled to Miami, leaving behind expropriated property. In their place, a new political elite formed, tied to the Communist Party and the revolutionary government. As in other communist systems, personal wealth accumulation was frowned upon, but insiders still enjoyed better access to scarce goods and exclusive privileges.

Pol Pot (Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, 1975–1979)

Pol Pot’s radical vision of an agrarian utopia meant the complete eradication of existing social classes and the elimination of “wealth” as a concept. The Khmer Rouge forcibly emptied cities, abolishing money and private property. The regime sought to establish absolute equality, but in practice, top Khmer Rouge officials still controlled resources, food distribution, and security. This extreme approach decimated Cambodia’s economic and cultural life, resulting in one of the most catastrophic social collapses in modern history.

Nicolae Ceaușescu (Romania, 1965–1989)

Ceaușescu’s brand of nationalism and communism led to the nationalization of most industries. While pre-communist elites had long since lost their status under prior Soviet-aligned regimes, Ceaușescu cultivated a new inner circle—a bureaucratic elite that enjoyed privileges like special shops and luxury goods. However, due to his obsession with paying off foreign debt and grandiose projects (such as the Palace of the Parliament), the country endured severe austerity measures. Ordinary people suffered shortages, while the leader and his close associates maintained a comparatively comfortable lifestyle. The very notion of “wealth” was thus bound up in one’s proximity to Ceaușescu while independent economic power non-existent.

In every case of an authoritarian ruler, “wealth” in a traditional sense became far less secure under these dictators than it might be in a system with stronger rule of law or a democracy. Economic power was tied directly to political favor, underscoring that with authoritarians, loyalty to the regime often outweighed any purely economic asset.

What comes next?

Schools are more than just places for learning because they are key public institutions that reflect and reinforce a society’s values and priorities. Schools ensure that students are fed, cared for, and given equitable access to education regardless of disability or income level. Public education shapes how history is taught and what truths are emphasized or omitted meaning that the policies governing schools have profound impacts on democratic life.

When federal support is withdrawn—especially from critical services like care for disabled students or free meals—education becomes less about equal opportunity and more about survival for the most vulnerable. This shift creates ideal conditions for authoritarian narratives to take hold, as people preoccupied with meeting basic needs can become more susceptible to leaders who promise simple fixes and prosperity.

History shows that authoritarian regimes focus sharply on education to reshape national identities, erase inconvenient truths, and propagate rigid ideologies. By controlling what schools teach, who funds them, and how they operate, dictators ensure a future generation grows up with a narrow, state-approved worldview.

While the United States still has some remaining checks and balances (for now) preventing an overnight transformation of the education system, calls for “patriotic education” and threats to dismantle the Department of Education echo tactics used by authoritarian leaders across the world to:

Altering curricula to a nationalist narrative instead of historical facts.

Suppressing dissent excluding minority voices and participation.

Consolidating power, money, and political influence into an elite group of ultra-wealthy loyalists.

Maintaining a strong, well-funded public education system—one that fosters critical thinking and meets students’ diverse needs—is essential to safeguarding democratic values and ensuring that all children (not just the wealthiest or politically favored demographic) have a fair chance to learn and thrive in society.

David Riedman is the creator of the K-12 School Shooting Database, Chief Data Officer at a global risk management firm, and a tenure-track professor. Listen to my weekly podcast—Back to School Shootings—or my recent interviews on Freakonomics Radio, New England Journal of Medicine, and my article on CNN about AI and school security.

A robust endorsement of public education and it’s critical role in democracy. Thank you!