Columbine's 'MONSTERS next door' and cultural rituals of school shootings

Why do we talk so much about "unspeakable" acts of violence? In literature, monsters mirror the culture they inhabit and serve to absolve society of responsibility.

This article is a collaboration with Georgetown University professor Rev. Dr. Ed Ingebretsen, an expert in monsters, cultural studies, and the author of At Stake: Monsters and the Rhetoric of Fear in Public Culture. You can also listen to our podcast about this article.

“The child who is not embraced by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth.”

- African Proverb

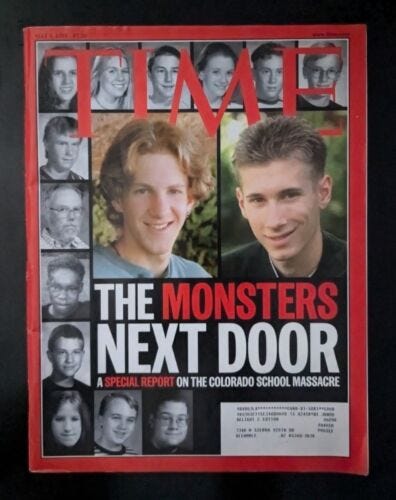

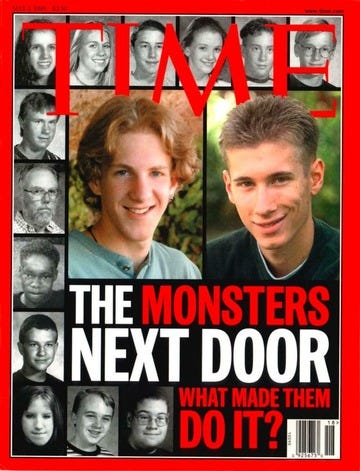

In 1999, TIME magazine printed a cover with smiling color photos of the Columbine school shooters surrounded by the partially obscured images of their victims in tiny black and white thumbnails. This overt glorification of these teenage boys is excused by one word in all caps and bright red: MONSTERS.

What does monster even mean and why are there 187 different film versions of Frankenstein?

The word "monster" carries a complex and multifaceted history, rooted in both etymological origins and cultural symbolism. Its evolution connects to ideas of critique, demonstration, and revelation, while also carrying religious connotations that blur the boundaries between fear, reverence, and warning.

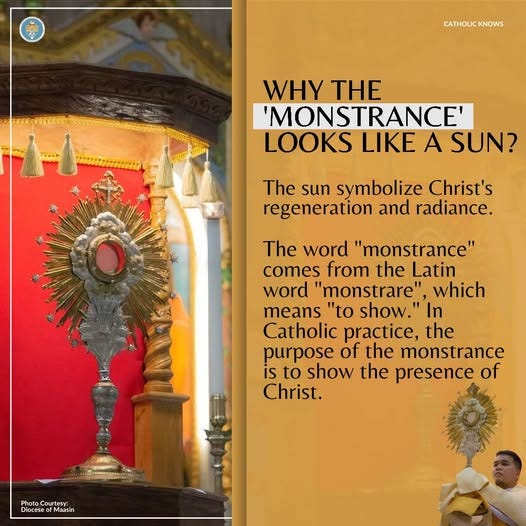

The Latin root monstro (to show, to point out, to advise, or to teach) also gives us the word "monstrance" in Catholic tradition. A monstrance is a sacred vessel used to display the consecrated Eucharist bread in a way that makes the host (bread) visible to the congregation. The monstrance functions as an instrument of revelation by holding up a symbol of the divine for all to witness.

This religious context adds a double-edged dimension to the term "monster." On one hand, the monstrance reveals the holy, the divine, and the good. But on the other hand, the "monster" defies both conventional form and social conformity. This reveals the dual nature of the monstrous: something that simultaneously attracts and repels. The monster draws attention to itself while serving as a warning of some underlying moral or existential crisis.

Simultaneously, the monstrous can also transcend its critique by pointing to something beyond human experience. In the realm of horror, monsters often embody existential fears about death, meaninglessness, or the unknown. They are symbols of that which cannot be fully grasped, of the chaos or void that lies beyond the human capacity for understanding.

What makes a monster? Each story carries the same seven elements (there’s a lot more about this in the final section below that’s adapted from Cohen’s Seven Thesis of Monster Culture):

The monster’s body is a cultural body: Monsters embody the anxieties, taboos, and values of the cultures that create them by reflecting societal fears and desires through their physical forms.

The monster always escapes: Despite attempts to contain or destroy it, the monster continually reemerges, symbolizing persistent cultural fears that evade permanent resolution.

The monster is the harbinger of category crisis: Monsters blur the lines between categories (e.g., human and animal; life and death) and this destabilizes social norms by challenging the boundaries.

The monster dwells at the gates of difference: Positioned at society's margins (the literal borders of civil society), monsters embody difference and otherness that highlights the societal anxieties about outsiders and marginalized identities.

The monster polices the borders of the possible: Monsters enforce societal limitations by defining what is permissible and what is taboo.

Fear of the monster is really a kind of desire: Monsters simultaneously evoke fear and fascination by embodying forbidden desires and impulses that society represses yet secretly longs to explore.

The monster stands at the threshold of becoming: Monsters prompt self-reflection and transformation by forcing societies to confront and reassess their norms and identities.

The word monster thus carries within it a profound tension because it critiques by revealing something essential while also serving as a metaphor for failure or transgression. But the monster is also for warning or transcendence. Whether in myth, religion, or modern storytelling, the monster shows us what we fear, but also what we need to reckon with. It gestures toward both the darkness in human nature and the divine truths that stand beyond human comprehension.

School Shooters are Monsters?

Cultural stories of the monster that date back centuries have four parts: The monster comes, the monster destroys, the monster must be destroyed, and it is not my fault.

Each of these four elements plays out during the social discourse following a school shooting:

The monster comes from some distant place that is separate from civil or mainstream society like the trench coat mafia, goth kids, mentally ill, loners, outcasts, and transgender.

The monster destroys the things a culture covets like innocent women and children inside a school.

The monster must die for cultural stability to return as police train to kill a teenage assailant, minors are sentenced to life in prison without parole, and politicians call for the death penalty for juvenile assailants.

The monster’s death cannot be my fault because even when families, communities, and institutions fail to protect vulnerable children who then turn their severe trauma into an act of mass violence, it’s rare for anyone beyond the young teens to be held accountable.

We have hundreds of years of English literature about monsters and 187 different film versions of Mary Shelley's 1818 novel Frankenstein. Like the original text of Frankenstein, the classic monster story is about a crisis where a monster appears and then needs to be vanquished from society. But these stories are not about fixing the root causes of what created the monster in the first place. They serve as a cartoonification of complex cultural and social issues by creating a binary, moral tale with a simple solution...the monster must die and it can’t be my fault.

When a school shooter is labeled a monster, there isn’t a simple binary cause, explanation, or fault to blame. An example is the CVPA High shooting in St. Louis.

Complex Issue: Suicidal teen was hospitalized for mental health treatment multiple times, talked about committing self-harm and violence, and wrote about his plans to commit a school shooting. A broken mental health system couldn’t help him, and broken state laws allowed him to buy an AR-15 rifle. Despite warnings from his family to police, he committed a school shooting and suicide-by-cop after months of planning and overt warnings.

Simple Binary: Loner without friends attacks a school.

The purpose of the monster story is to show us this problem because when there are complex issues that remain unresolved, every culture gets the monster it deserves.

Who are these monsters?

What do school shooters like Erik Kleibold, Nikolas Cruz, Salvador Ramos, Seung-Hui Cho, and Adam Lanzo have in common? Each of these individuals has been named “a monster” by the media.

The label functions as a way to express public outrage, captures the moral gravity of the crime, and removes the individual from judicial due process because the monster must die and it cannot be our fault. For example, the Florida Senate passed a bill repealing a law requiring a unanimous jury recommendation for the death penalty after a divided jury spared the Nikolas Cruz from capital punishment.

Republican Sen. Blaise Ingoglia, the bill sponsor said “that verdict shocked the conscience not only of the people of Parkland, not only the people in Florida, but people across the United States of America” because…the monster must die.

The term "monster" is often used in media narratives about school shooters to emphasize the inhuman and incomprehensible nature of their actions. Here are some notable examples:

1. Adam Lanza (Sandy Hook Elementary School Shooting, 2012)

Use of "Monster": After Lanza's attack on Sandy Hook Elementary, media outlets, victims’ families, and commentators frequently referred to him as a "monster." The term was used to underscore the brutality of his crime, especially given that many of the victims were young children. His cold, detached persona and the violence of his actions made him an emblem of pure malevolence.

Rationale: His actions were seen as so heinous and incomprehensible that they were framed as beyond human, thereby justifying the "monster" label.

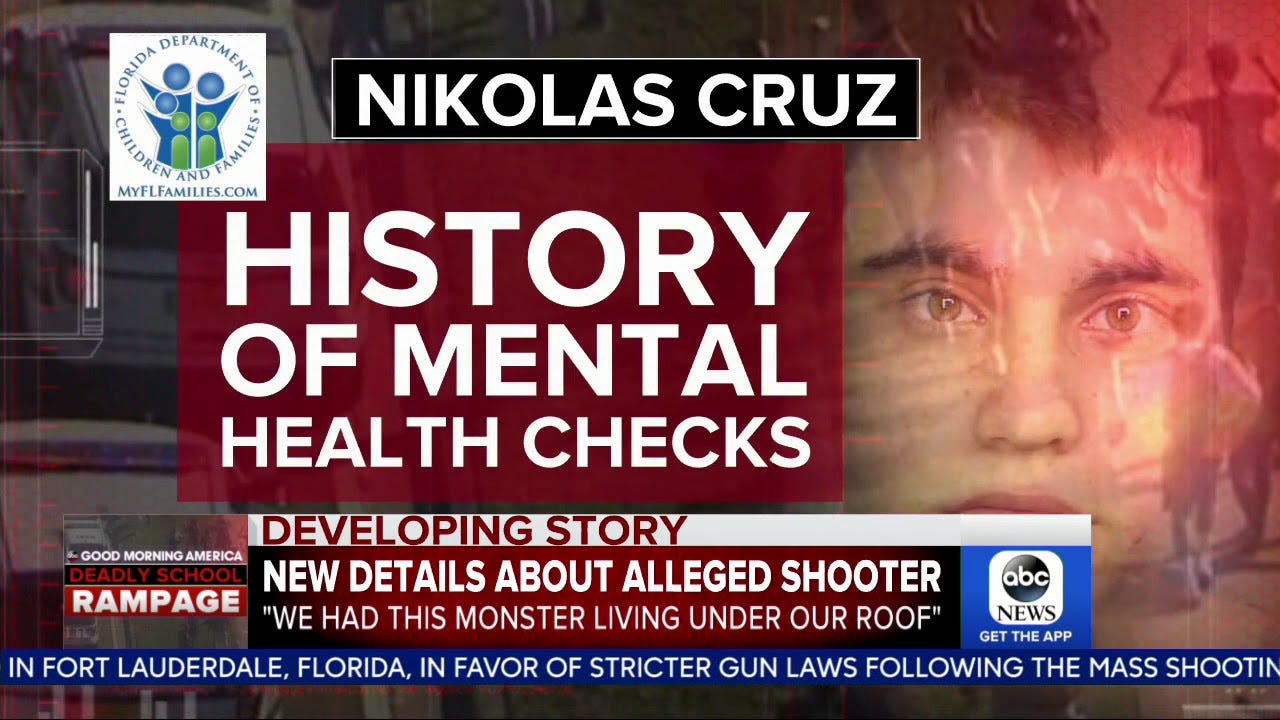

2. Nikolas Cruz (Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Shooting, 2018)

Use of "Monster": Following the shooting in Parkland, FL, Nikolas Cruz was often labeled a "monster" by both the media and survivors. His premeditated attack and apparent lack of remorse contributed to this dehumanizing characterization: “We had this monster living under our roof”.

Rationale: Cruz’s calculated method, use of social media to hint at his violent intentions beforehand, and the devastating toll on the school and community painted him as a monstrous figure.

3. Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold (Columbine High School Shooting, 1999)

Use of "Monster": Harris and Klebold, who committed the Columbine High School massacre, were repeatedly described as "monsters" in the aftermath of the attack. Their carefully planned attacked and the detailed journals they left behind explaining their motives, amplified their portrayal as monstrous in both media and public opinion.

Rationale: Their violent fantasies, desire for mass destruction, and targeting of their peers and teachers were framed as monstrous by a society struggling to comprehend their actions.

4. Elliot Rodger (Isla Vista Killings, 2014)

Use of "Monster": Though his attack primarily targeted women at random, Elliot Rodger’s rampage, which also involved a school, was often discussed in media narratives with the label of "monster". Rodger’s misogynistic manifesto, in which he described his plans to enact violence due to his perceived rejection by women, contributed to his monstrous portrayal.

Rationale: Rodger’s explicit hatred for women, as outlined in his writings, and the premeditated nature of his attack, made it easy for the media to reduce him to the archetype of a "monster."

5. Seung-Hui Cho (Virginia Tech Shooting, 2007)

Use of "Monster": After Cho killed 32 people in the deadliest school shooting in U.S. history, he was frequently labeled a "monster" by the media. His violent videos and writings, which expressed a deep sense of alienation and a desire for revenge, contributed to the public perception of him as an inhuman figure.

Rationale: Cho’s profound detachment from society and his desire to inflict mass suffering were portrayed as traits that made him more of a "monster" than a human being.

These deeply ingrained cultural stories of monsters are not unique to the United States. While the words used to describe school shooters in other countries might not directly be 'monster', equivalent terms are often used that emphasize their inhumanity and the shock their actions provoke.

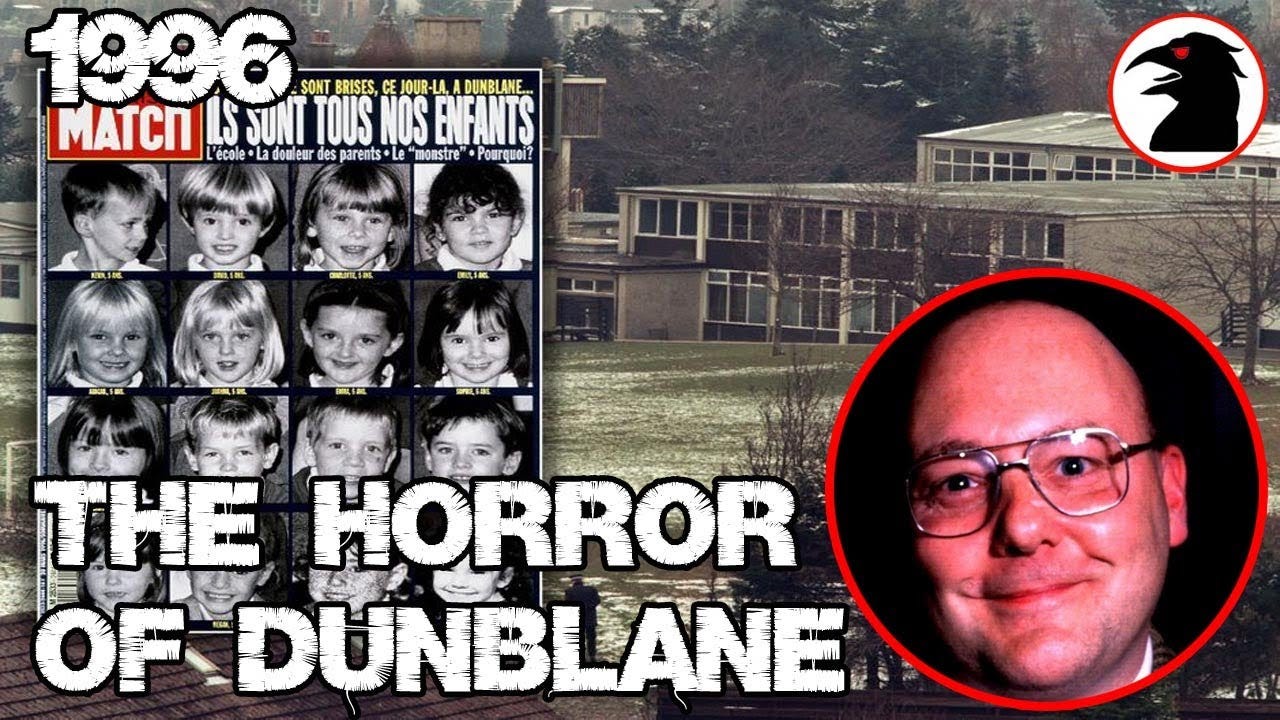

1. Dunblane Massacre (Scotland, 1996) – Thomas Hamilton

Term Used: In the U.K., after Thomas Hamilton killed 16 children and a teacher at Dunblane Primary School, he was often referred to in media reports as “the horror of Dunblane”, a "beast", or "fiend", which carry similar connotations to "monster." These terms emphasized his inhuman, almost animalistic predatory nature, given the atrocity of killing young children.

Rationale: Hamilton's actions were framed as the embodiment of evil (e.g., The Horror), as he attacked the most vulnerable members of society. These labels helped to express society's collective horror and incomprehension of his acts.

2. Erfurt School Shooting (Germany, 2002) – Robert Steinhäuser

Term Used: In Germany, after the Erfurt school shooting, Robert Steinhäuser was labeled a "Ungeheuer" (which translates to "monster" or "fiend") in media coverage. The term highlighted the enormity of his violence after he killed 16 people, including teachers and students, before taking his own life.

Rationale: The label "Ungeheuer" signified Steinhäuser’s actions as beyond human comprehension, focusing on the extreme nature of his crime in a typically peaceful environment.

3. Kerch Polytechnic Massacre (Crimea, 2018) – Vladislav Roslyakov

Term Used: Russian media used terms like "маниак" ("maniac") and "зверь" ("beast") to describe Vladislav Roslyakov after he killed 20 students and teachers. These terms are equivalent to "monster" in English, reflecting the brutality and senselessness of the attack.

Rationale: In this case, the language was used to signify Roslyakov’s complete lack of empathy and the sheer terror he inflicted on his victims. The label "beast" dehumanized him and cast him as an animal acting separately from human society.

4. Colégio Raul Brasil Shooting (Brazil, 2019) – Guilherme Taucci and Luiz de Castro

Term Used: In Brazil, after the São Paulo school shooting, the media referred to the shooters as "monstros" ("monsters").

Rationale: The term "monster" was used to express the community's revulsion and that his actions were far beyond the realm of normal human behavior.

5. Jokela School Shooting (Finland, 2007) – Pekka-Eric Auvinen

Term Used: Finnish media and public discourse often described Pekka-Eric Auvinen as a "hirviö" (Finnish for "monster"). After he killed 8 people at his school, the label reflected the widespread shock and horror, portraying him as an aberration of humanity.

Rationale: The term was meant to capture the moral outrage felt by the Finnish public, emphasizing the deep societal rupture caused by such a violent act in a typically peaceful environment.

‘No Notoriety’ movement follows the monster story

The ‘no notoriety’ movement encourages the media not to share the names and images of school shooters. But instead of preventing violence, this concept is an extension of the monster story used to absolve us from responsibility by creating a nameless and faceless nonhuman to blame.

While it seems like a good idea not to glorify and idolize mass murderers, not naming or showing photos just hides their identity from casual observers (like parents) who watch network news.

Kids can find out anything they want to know about school shootings and mass shootings on thousands of internet forums with pictures, videos, discussion boards, and even fan art idolizing the attackers. Since Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram removed the content moderation teams, children and teens can easily find violent content that glorifies school shootings. Every parent should also understand how Discord works and why the school shooting community content on distributed private servers isn’t moderated.

Instead of pretending like school shooters aren’t human—the foundation of monster making stories that absolves us of responsibility—parents need to be able to immediately recognize their faces, names, nicknames, and symbols associated with school shooters.

For parents to spot red flags, they need to know who and what to look for. Monsters are a representation of the cultural spaces they inhabit. Pretending like they don’t exist feeds the narrative and helps create the next one.

Non-Human Terminology

Why do ambiguous terms that don’t align with legal statutes or criminal charges like “school shooter”, “active shooter”, or “mass shooter” exist? Why aren’t the offenders just called murderers?

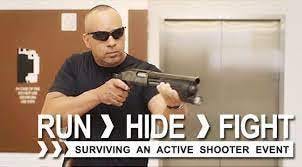

The literary tools for monster making and otherness are apparent in the very first active shooter training video created by a Hollywood production company for the City of Houston in 2012 (viewed more than 11 million times). This video was released 5 months before the school shooting at Sandy Hook. Prior to this video and Sandy Hook, the term active shooter was not part of common dialogue for the American public.

The video opens with a cheery narrator saying: “some days life feels more like an action movie than reality”.

As you watch this video, which character gets the most screentime at the center of the frame? Is the purpose of this video to Run, Hide, Fight a monster…or is it an instructional guide for making a monster?

The monster story tells us how to make one:

The monster’s body is a cultural body: In Run, Hide, Fight, the “active shooter” is not just an individual committing a violent act—they are constructed as a symbol of cultural anxiety. The shooter’s appearance is intentionally vague: generic clothing, emotionless expression, no clear motive. This lack of specificity allows viewers to project their own fears onto the figure, turning him into a repository for societal dread about safety, strangers, mental illness, masculinity, or the failure of institutions. The shooter’s body becomes a stand-in for whatever cultural moment the viewer fears most.

The monster always escapes: Though the video ends with the shooter neutralized or the threat subsided, the message is clear: this will happen again. The training doesn’t resolve fear—it sustains it. “Be prepared” implies the monster is never truly gone. Like the classic horror villain who reappears in the sequel, the “active shooter” is an ever-present specter. The body may fall, but the category—the active shooter threat—remains alive and mobile.

The monster is the harbinger of category crisis: The active shooter is an ambiguous figure: not military, not terrorist (in the official sense), not clearly criminal until the moment of violence. They don’t fit neatly into legal or social categories. This disruption of identity—is someone a coworker or a killer? Are they a student or a threat?—creates a cognitive rupture. The video does not resolve this confusion, rather it exploits the categorical crisis. The monster destabilizes our assumptions about where danger comes from and what it looks like. That uncertainty is part of its power.

The monster dwells at the gates of difference: Although the shooter is often portrayed as familiar—an “ordinary” person—there is always a trace of difference emphasized in subtle ways: they move differently, behave erratically, are emotionally cold or detached. These cues mark them as other, even if superficially they appear the same as everyone else. The training video teaches viewers to look for these signs, reinforcing a sense of suspicion toward anyone who seems different. The monster is thus someone within—but not quite of—the group.

The monster polices the borders of the possible: By showing what the monster can do—invade a workplace, school, or mall—the video expands the realm of what is imaginable, and therefore what must be feared. It reshapes public consciousness around space and behavior because normal places are now potential war zones and everyday routines demand tactical thinking. In this way, the monster defines what’s plausible in the cultural imagination, narrowing the margin of safety and expanding the realm of threat.

Fear of the monster is really a kind of desire: The active shooter, though presented as purely monstrous, also captivates public attention and imagination. Society fixates on these events through media because they permit exploration of suppressed anxieties and desires—control, powerlessness, heroism, violence—under the safe guise of preparation. The fear, paradoxically, also becomes a kind of fascination, a space where cultural taboos and repressed desires around violence and heroism can be simultaneously indulged and condemned. How deadly can my AR-15 rifle really be? Few gun owners get to use their rifles for the designed purpose of killing other humans. Each school shooting is a chance to witness and fanaticize about the power their weapon has.

The monster stands at the threshold of becoming: By embedding the active shooter in everyday scenarios—schools, offices, public spaces—the training video not only warns about external threats but also compels self-examination and transformation. The shooter’s ambiguous identity reflects back upon society itself, forcing uncomfortable questions about community, safety, alienation, and trust. In this reflection, the monster prompts society to redefine itself, continuously renegotiating what behaviors, conditions, or policies must be adopted or abandoned in the quest to keep monstrous violence at bay.

It’s striking how closely the active shooter training video parallels any Frankenstein or horror movie. The 1944 film House of Frankenstein and the Homeland Security Run, Hide, Fight video both operate within the genre logic of horror, using cinematic tools to construct a monster that embodies cultural fear. In House of Frankenstein, the monster is a composite of others that are stitched together into a spectacle of uncontrollable threat. Similarly, the active shooter in the Homeland Security video is not a specific person with a clear motive, but an amalgamation of traits designed to provoke fear: emotionless, silent, anonymous. Both center the monster in the frame, using lighting, sound, and pacing to amplify suspense. Importantly, neither monster is fully explained—they exist to terrorize and to justify the need for constant vigilance (or surveillance).

Just as House of Frankenstein channels wartime anxieties into monstrous forms, the Run, Hide, Fight video translates post-9/11 and post-Sandy Hook fears into a visual narrative that reinforces who the monster is and how we should respond. In both cases, the viewer is not just watching a story unfold, they are told they are living within it.

The terms “school shooter,” “active shooter,” and “mass shooter” persist not because they align with legal definitions, but because they serve a different, cultural function. These labels do not name a crime—they conjure a figure. Unlike the term “murderer,” which is direct and grounded in law, these ambiguous descriptors evoke archetypes and anxieties. They open space for myth-making, allowing us to cast certain people as monsters rather than forcing us to confront the systemic and human factors behind violence.

The 2012 Run, Hide, Fight video exemplifies this shift. Rather than teaching preparedness, it visually codes the “active shooter” like a creature in a horror film. The man walking with a gun is centered in the frame, stripped of context, and defined only by threat. Just as in House of Frankenstein, the monster becomes a vessel for our fears, our failures, and our fascination. By naming the monster but not the act—by refusing the legal term “murderer”—we distance ourselves from responsibility and complexity.

In the end, perhaps these terms exist not to describe what happened, but to narrate what we fear might happen again while absolving ourselves from responsibility for the monster we all helped to create.

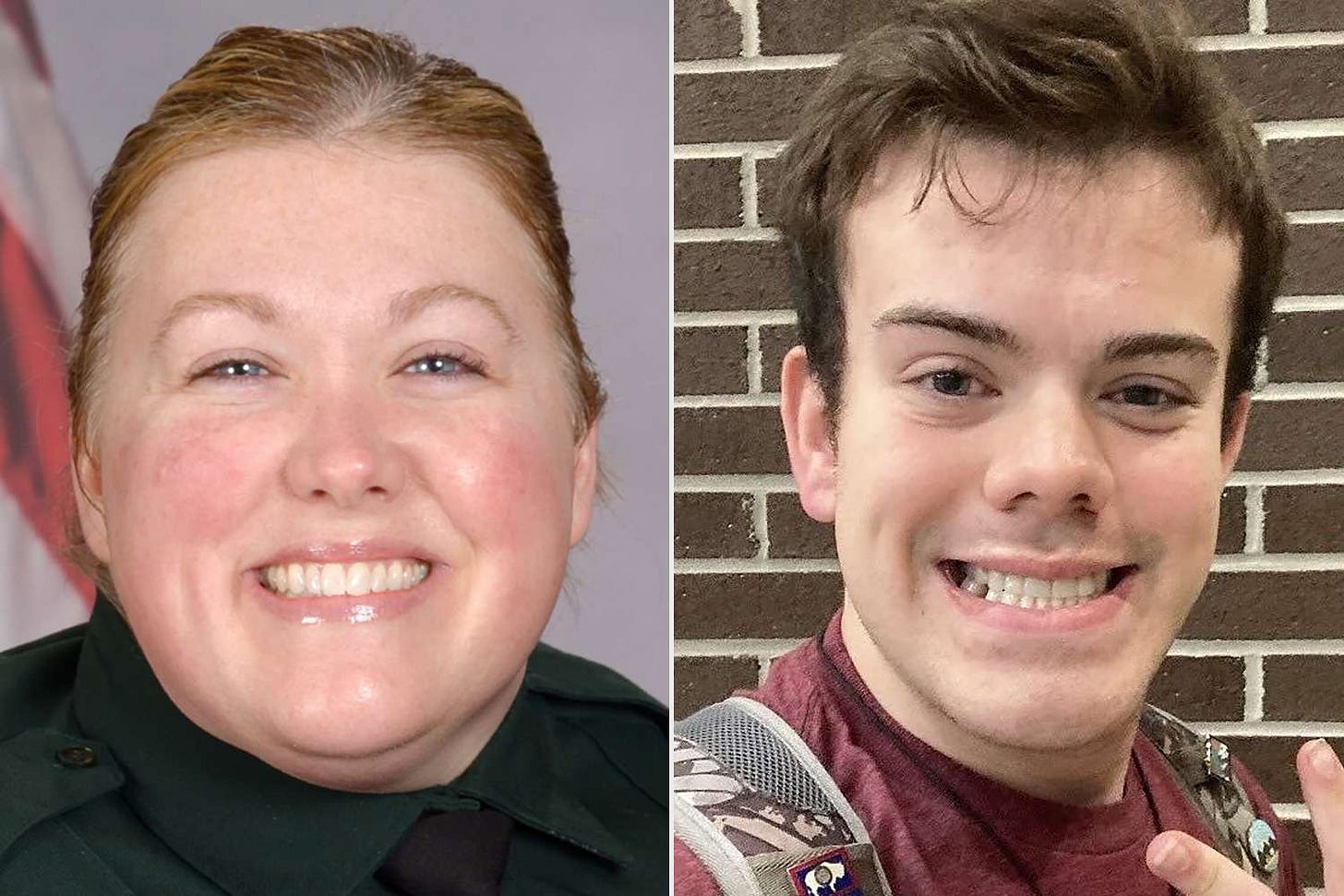

Florida State University Shooting

The day before I planned to publish this article (scheduled for Good Friday before Columbine), there was another school shooting at FSU in Tallahassee, FL. A 20-year-old student opened fire near the Student Union killing two and critically injuring five others.

Hours after the shooting, we learned he is the son of a long-serving and well-respected member of the local police department. He also attended police training programs, was a member of the police youth advisory council, and used his mother’s department-issued gun to commit the shooting.

This information creates a category crisis. How can someone be:

“Steeped in the Leon County Sheriff's Office family" and a mass murderer

Smiling young FSU student and a mass murderer

Good guy trained to use a good guy’s gun and a mass murderer

To address this impossibly complex problem of duality and societal failure, he is predictably labeled a monster.

Learn More

Monster Culture (Seven Theses) - Jeffrey Jerome Cohen

At Stake: Monsters and the Rhetoric of Fear in Public Culture - Rev. Dr. Edward J. Ingebretsen

Monster-Making: A Politics of Persuasion - Rev. Dr. Edward J. Ingebretsen

Interdisciplinary studies can be a really interesting way to explore topics from an outside perspective. If you missed it, take a look back at Ep 23: What can dance and performance teach us about lockdown drills? Shannon Woods, PhDc, explains her new paper 'The Threat Is Now: Choreography, Temporality, and the Active Shooter Drill'.

David Riedman is the creator of the K-12 School Shooting Database, Chief Data Officer at a global risk management firm, and a tenure-track professor. Listen to my weekly podcast—Back to School Shootings—or my recent interviews on Freakonomics Radio, New England Journal of Medicine, and my article on CNN about AI and school security.