Active Shooter: Armed Samaritans Present More Risks than Reward

In March 2016, two brothers launched an unprovoked attack on Prince George’s County (MD) police headquarters, indiscriminately firing at…

In March 2016, two brothers launched an unprovoked attack on Prince George’s County (MD) police headquarters, indiscriminately firing at the building, officers, and passing vehicles.

That’s when Officer Jacai Colson, a narcotics detective, was arriving at headquarters in an unmarked vehicle. He found himself in the middle of the gunfight. Unfortunately, amid the chaos, Officer Colson was shot and killed by another Prince George’s County police officer. (WUSA)

Officer Colson was dressed in plain clothes with no identifiable badge or agency logo. In the literal heat of the battle, four different officers mistakenly fired upon him. This occurred solely due to confusion, stress, lack of situational awareness, overwhelming stimuli, and the adversary’s tactical advantage from the surprise attack. There was no intent to kill another police officer, and the fellow officer who fired the fatal shot was not charged.

This is not a commentary on gun control. Wild game and waterfowl hunting are enjoyable and rewarding hobbies. Friends can enjoy shooting trap and skeet in the same casual manner that many choose to play golf. Target shootings requires skill, patience, focus, attention to detail, and practice. Kids can harmlessly spend their summer afternoons plinking cans with .22 rifles.

In the wake of each mass shooting, the narrative of good guys with guns can stop a bad guy with a gun arises. On the surface it may seem to be a logical assumption, but our most highly trained warriors and officers frequently make wrong decisions on the battlefield. An armed private citizen taking action against an active shooter with a fraction of the professionals’ training, equipment, and supporting command/control structure is positioned to make tragic mistakes with fatal consequences.

Friendly Fire on the Battlefield

The battlefield is chaotic. Friendlies and enemies move and fire from multiple directions. U.S. operations occur simultaneously from land, sea, and air. Movements of some units are directed from the battlefield while others receive orders from command centers across the world.

An analysis of U.S. Army friendly fire incidents in Iraq and Afghanistan between 2001 and 2008 showed common themes across nearly all of the incidents.

From these data, the most common causes of U.S. fratricide accidents were related to the categories “Misidentification,” “Teamwork,” and “Procedures.” Common findings related to “Misidentification” included combat identification measures, the actions of the target, and the physical features of the target. The majority of the findings under the “Teamwork” category were related to leadership issues, and most of the findings under the “Procedures” category involved fire control and discipline. In fact, the leadership sub-category had the greatest number of occurrences of all 57 sub-categories. A total of 98 findings were identified with the FCAS analysis (see appendix C for frequency data for specific FCAS categories). Other common causal factors include confidence and training. (USAARL Report 2010–14)

In the heat of battle, well trained soldiers failed to properly differentiate enemies from allies due to a lack of command/control, incomplete information, inadequate procedures, and inability to visually identify targets. During a gun fight — magnified by an ambush — , it’s hard to figure out what is going on, where the fire is coming from, where your other units are, and who is shooting at who. An armed Samaritan in the middle of an active shooter’s ambush has no command and control element, no information about the shooter or other friendlies/police, and no procedures directing action. The leading cause of the U.S. Army’s incidents were rooted in fire control and discipline…the final split-second when a soldier looks down the barrel at a target and must decide to pull the trigger or not.

If professional soldiers operating in a strict command structure with state-of-the-art weapons, optics, and communications systems still accidentally fire on the wrong targets, the cards are stacked against the lone citizen with a concealed handgun and no support structure.

Police and Fatal Shootings of Unarmed Suspects

Police officers are involved in approximately 1,000 fatal shootings across the United States every year. While many of the shootings are justified, other are a result of miscommunication and misinterpretation (e.g., in the dark the wallet looked like a gun).

The Washington Post breaks down police involved shootings in detail:

“Good cops judge when they can hold back,” said Geoffrey Alpert, a criminologist at the University of South Carolina who has studied pursuits for three decades. “So what if you get pushed in a volatile domestic situation? You’re justified to use force, but you tactically withdraw, calm them down and move on.”

Still, Rob Ord, a longtime instructor on defensive police tactics who now runs Falken Industries, a Virginia security company, said, “It’s almost always better to back off and call for help.”

Taking immediate action against an active shooter is the opposite of the guidance given to police officers. It is important to back away from danger, assess the situation, and form a plan before taking action.

Cognitive Challenges

Malcolm Gladwell’s best selling book Blink includes a detailed account of the accidental — but fatal — shooting of Amadou Diallo by NYPD officers in 1999. Diallo reached for his wallet and was shot 41 times by four different officers. In one officer’s account of the shooting:

Shots are still going off. I’m running. I’m moving. And Ed was shot. That’s all I could see. Ed was firing his weapon. Sean was firing his weapon into the vestibule…. And then I see Mr. Diallo. He is in the rear of the vestibule, in the back, towards the back wall, where that inner door is. He is a little bit off to the side of that door and he is crouched. He is crouched and he has his hand out and I see a gun. And I said, ‘My God, I’m going to die.’ I fired my weapon.

All four officers had a similar account and following the shooting:

Carroll and McMellon fired sixteen shots each: an entire clip. Boss fired five shots. Murphy fired four shots. There was silence. Guns drawn, they climbed the stairs and approached Diallo. “I seen his right hand,” Boss said later. “It was out from his body. His palm was open. And where there should have been a gun, there was a wallet…. I said, ‘Where’s the fucking gun?’”

Later, when the ambulances arrived, Boss was so distraught, he could not speak. Carroll sat down on the steps, next to Diallo’s bullet-ridden body, and started to cry.

The officers did not intend to kill an unarmed man. The human brain is not wired to rapidly assess overwhelming stimuli during intense stress. All four of the officers had a failure of rapid cognition due to the physiological impacts of intense stress on the body. In a perceived life or death situation, your heart rate quickly rises about 175 beats per minute and you lose the ability to complete basic motor and sensory tasks. Under intense stress, police officers firing guns recounted that their field of vision was diminished (tunnel vision), time slowed down, sounds were not heard, distances were not perceived, and some did not even remember firing their weapons.

An armed Samaritan caught in the middle of a surprise attack by an active shooter will instantly be exposed to extreme physiological stress that will inhibit their cognitive ability to accurately assess the situation and make critical decisions to fire their gun or not. Highly trained police officers make the wrong interpretations and decisions under these extreme circumstances — it is unlikely that the armed Samaritan will perform better.

Pulling the Trigger: Low Certainty, High Consequences

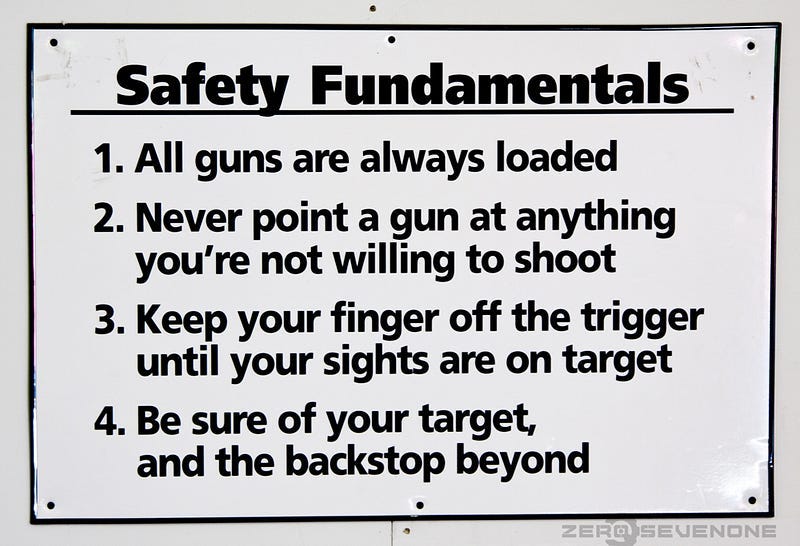

The fundamental rule of firearms safety is only point a gun at something you are ready to kill. Your target includes everything behind it. Your finger only touches the trigger when you are sure of the target and the backstop behind it is clear.

In a crowded movie theater, shopping mall, church, night club, or any of the public areas that active shooters have targeted, are you confident that you can identify the right target and maintain a clear backstop?

In April 2015, a man walked into a busy suburban Maryland shopping mall and fatally shot his ex-girlfriend. He immediately committed suicide after killing her. This was a public homicide, not an active shooter. There was a premeditated target and nobody else was in danger. This would would not be immediately apparent to an armed Samaritan near the shooting. What happens when you misidentify a shooter and hit another bystander? Your bullets are as damaging as the shooter’s. What if this public homicide was repeated inside a movie theater? Would you be able to confidently assess the situation and make a clear shot? The chances of injuring or killing someone else are enormously high. Once you have hit the wrong person, you are as — or even more — damaging and dangerous than the original shooter.

What If? Armed Samaritans at the Batman Theater Shooting

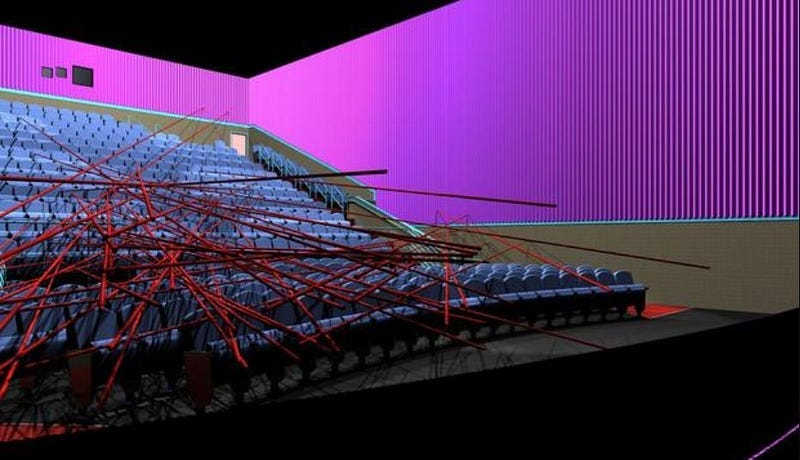

The Batman movie starts. An sensory-rich opening credits scene plays with booming bass and the screen rapidly flashing between bright white and dark images. An active shooter enters the theater and throws a can of OC gas (a powerful respiratory and mucous membrane irritant). The shooter walks to the corner of the screen in the front of the theater and begins firing indiscriminately into the crowded theater.

Armed Samaritan #1 is seated on the right side of the theater. He sees a series of bright muzzle flashes and people begin to scream. The OC gas causes his eye to tear, mucous to stream from his nose, and uncontrollable coughing. Between the flashes of bright light from the screen, AS #1 identifies the shooter, draws his concealed pistol, and fires at the shooter.

Armed Samaritan #2 is seated on the left, lower side of the theater. The shooting is occurring behind him and he does not immediately distinguish it from the audio of the movie opening. Once people start screaming, he turns around and observes muzzle flashes from the center of the crowd in the theater. He then sees a second shooter at the edge of the aisle between the rows of seats. He is hit by the OC gas and begins to blink back tears. Armed Samaritan #2 takes aim at the shooter in the middle of the theater and begins firing his pistol.

People running from the theater are calling 911 and reporting 3 different shooters carrying out a coordinated attack. The first arriving officer decides that they need to stage until back-up arrives because this is not a single active shooter and they are outnumbered. In the theater, the active shooter continues to fire at the crowd while AS #1 and AS #2 fire at each other and strike additional victims in the process.

12 people were killed in the 2012 Aurora Theater Shooting. If there had been armed Samaritans in the theater who decided to fire back during the shooting, it is more than likely that the death toll would have been even higher. In a dark theater, there is no way to gather information about the situation to identify the bad guy, ensure that the backstop is clear, and justify the use of deadly force.

Who is THE shooter?

As soon as you draw your weapon, you are indistinguishable from the active shooter. During the 2013 shooting at the Navy Yard in Washington, DC, dozens of plain clothes officers from multiple agencies responded to the scene. Bystanders at the scene called 911 with multiple descriptions and locations of the shooter because they confused plain clothes officers with the attacker. The confusion caused by the misinterpretation of good guys versus bad guys causes misdirection and waste of critical time and resources. During the recent Las Vegas shooting, there were continued reports of multiple shooters and it took 72 minutes to declare the “all clear” when the shooter had already been dead for more than an hour.

An armed Samaritan holding a gun instantly becomes a second shooter. How do arriving police officers know who the shooter is when there are multiple citizens with guns? What stops another armed Samaritan from mistaking you from the shooter? How do you know that you are shooting at the active shooter not another armed Samaritan? If an innocent bystander is caught in the crossfire and struck by your bullet, are you as guilty (in the moral, ethical, and legal sense) as the original shooter?

Words of Wisdom from the Professionals

When police officers find themselves in the middle of chaotic scenes, they back away to safe distance, call for more officers, assess the situation, formulate a plan, and then take action as a team. An armed Samaritan in the middle of an active shooter situation does not have any of these options.

Pulling the trigger is a decision that has deadly consequences. Professionally trained soldiers and police officers still make the wrong decisions when they are surprised, under intense stress, don’t have enough information, are unable to communicate with other officers, don’t know what the target looks like, and don’t have situational awareness of the big picture. An armed Samaritan in the middle of an active shooter situation is experiencing all of these contributing circumstances that result in poor decision-making and mistakes on the battlefield.

You can only kill if you point your gun. If you feel the overwhelming need to carry a firearm, keep it in the holster until you know exactly what is going on, who the shooter is, who all of the other good guys are, and that your backstop is 100% clear. If you leave your gun in the safe, you don’t need to worry about any of this in a public space.

When you use lethal force, a bad decision can change, or end, countless lives. If a bad guy has a gun, a good guy with another gun can create even more confusion that results in unintended and fatal consequences. Before an accidental tragedy happens, it’s your choice to never be in that position.

For more information about what actions to take following an attack, please read my previous article: Active Shooter: When you can’t run, can’t hide, and can’t fight. A personnel-sized trauma kit with a tourniquet will absolutely save lives following a shooting.

David Riedman is the creator of the K-12 School Shooting Database and a national expert on school shootings. Listen to my recent interviews on Freakonomics Radio, New England Journal of Medicine, and Iowa Public Radio the day after the Perry High shooting.